by Oliver Wainwright

The Guardian, Tuesday 26 February 2013

‘Ruins in reverse’ … the National Assembly in Dhaka.

Louis Kahn used to tell his students: if you are ever stuck for inspiration, ask your materials for advice. “You say to a brick, ‘What do you want, brick?’ And brick says to you, ‘I like an arch.’ And you say to brick, ‘Look, I want one, too, but arches are expensive and I can use a concrete lintel.’ And then you say: ‘What do you think of that, brick?’ Brick says: ‘I like an arch.'”

Believing his materials had a stubborn sense of their own destiny was one of the many quirks of this oddball architect, who died of a heart attack in a toilet at New York’s Penn Station in 1974. His body went unclaimed for four days, as the much praised 2003 film My Architect, made by his son Nathaniel, detailed. A vast new retrospective of Kahn’s work has just opened at the extravagantly contoured Vitra Design Museum in the German town of Weil am Rhein. Kahn, a conjuror of strange, monumental forms that have the gravity of ancient ruins, was one of the most influential architects of the 20th century – yet, even after that film, he is still one of the least known. Why?

“His strange, quasi-religious utterances were all rather irritating to me and my generation,” says the exhibition’s curator, Stanislaus von Moos, an art historian who has produced definitive tomes on Le Corbusier and Robert Venturi. “He is very difficult to characterise. I had always admired his work, but found it a bit intimidating.”

Born in Estonia in 1901, the Jewish American brick-whisperer is most famous for a series of enormous institutional complexes that stand in swelteringly hot places: the laboratories of the Salk Institute in California; the Institute of Management at Ahmedabad in India, with its dynamic brick colonnades; and the brooding concrete fortress of the National Assembly in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

For Kahn, form did not necessarily follow function; nor did his projects celebrate all the new possibilities of industrial materials. Created from monolithic masonry, and drawing on primary geometries with great circles, semi-circles and triangles sliced out of their weighty walls, his buildings exude a timeless and sometimes sinister presence. They look like the hastily vacated remnants of a future cosmic civilisation.

Primary geometry … Kahn’s Salk Institute in California.

Much has been made of Kahn’s spiritual dimension, his ability to channel the ancients, but this exhibition, which arrives in London next year, strives to show the many other sides to his work. The result is a vivid picture of a curious man, with his obsessions – from utopian urban-planning to scientific discoveries of molecular structures – all brought to life through his personal ephemera and correspondence.

The show begins by placing Kahn in the context of Philadelphia. He arrived there as Leiser-Itze Schmulowsky, the child of poverty-stricken immigrants. Painfully near-sighted and severely scarred by facial burns, he was drawn to architecture at an early age, witnessing the radical remodelling of his city at first hand, as the scenic Benjamin Franklin Parkway sliced an axis of museums diagonally through its grid.

We see the Philadelphia of the 1950s as a laboratory for urbanism, sparking Kahn’s (unrealised) vision for the city as a network of pedestrian boulevards. He imagined all traffic banished to a ring of cylindrical multi-storey car parks each the size of the colosseum – foreshadowing our contemporary park-and-ride culture. The structures have a hi-tech, crystalline quality, revealing that fascination with the natural sciences and the beginnings of his search for geometric order.

It is an obsession vividly demonstrated by his model for City Hall Tower, a spiralling double helix based on Francis Crick and James Watson’s discovery of DNA in 1953. Far ahead of its time, it was never built, but would go on to inspire the clustered tower structures of the Japanese Metabolism movement in the 1960s and 70s, as well as Norman Foster’s more recent triangular-patterned Hearst Tower in New York.

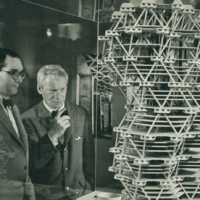

Louis Kahn (right) in front of a model of the City Tower Project in an exhibition at Cornell University, New York, February 1958

Never one to try too hard to ingratiate himself with his clients, it wasn’t until he was in his early 50s that Kahn completed his first major building: the rigidly cubic Yale University Art Gallery. By the time he was 60, this short man who wore loose bowties and combed his hair forward to hide his baldness had risen to international prominence, building the Richards Medical Laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania. Comprising stacked towers of column-free laboratories, this was the first of his projects to articulate the difference between “served and servant spaces” – the latter being stairwells, airducts and other supportive networks. He housed these in separate, chimney-like structures echoing the towers of San Gimignano in Italy he had sketched a few years earlier.

These energetic pastel drawings depict ruined temples across the classical world, from Corinth to Rome, and Luxor to Giza. They dot the exhibition, alongside postcards home in which Kahn writes of long hours watching the changing light play across the stones. It was these trips, undertaken in the 1950s, that led him to believe that the essence of architecture was only truly revealed in its ruined state: devoid of function, a building could then speak solely of how it was made. This realisation came to define his most important work, completed over the next 20 years.

Kahn would describe his building sites as “ruins in reverse”. In Dhaka, this served him particularly well: legend has it that, during the Bangladesh liberation war of 1971, bombers spared the construction site of his National Assembly, taking the mysterious cellular complex to be the ruins of an ancient historic site. But, as the exhibition stresses, such layered shells were no aesthetic folly or indulgent fetish for the archaic. The Dhaka building’s perforated walls are a vital tool, protecting the interior spaces from direct sunlight and allowing passive ventilation. As Von Moos says: “We wanted to show that, behind this facade of neoclassicism and historic revival, he really embedded his buildings in an understanding of the environment.”

There is also some new film footage of his projects, shot by his son Nathaniel. My Architect painted a not altogether sympathetic picture of his father, who left behind three children by three different women. His complex personal life makes the section on his house designs all the more poignant, particularly in the full-scale reconstruction of an entire corner of the seminal cypress-clad Fisher House in Pennsylvania – which includes the very window seat where his three children meet to discuss their estranged father in the film.

Kahn was bankrupt when he died in that toilet at the age of 73, his small Philadelphia practice $500,000 in debt. Why did the body of such an eminent architect, who gave the 20th century some of its most spellbinding buildings, go unclaimed for so long? Apparently, the address in his passport had been mysteriously obliterated. Fortunately, as this show demonstrates, Kahn’s reputation is proving more durable.

• Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture is at the Vitra until August. It comes to the London Design Museum in 2014. Oliver Wainwright travelled courtesy of show sponsor Swarovski.