THE HERITAGE OF THE ROMAN SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND THE CANIGGIA’S NOTION OF ORGANISM

THE HERITAGE OF THE ROMAN SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND THE CANIGGIA’S NOTION OF ORGANISM

by Giuseppe Strappa

in: Gianfranco Caniggia Architetto, edited by Gian Luigi Maffei, Alinea, Florence 2003

- CRITICISM OF INTERNATIONAL MODERNISM

The figure of Gianfranco Caniggia, as a scholar and architect, must undoubtedly be studied inside the general background of continuity with his own cultural area, whose heritage – extensively dilapidated by Italian post-war architecture – was driven as much by “survivors” who contributed to the formation of the Roman School of Architecture between the two wars (Fasolo, Foschini and Piacentini) as by Saverio Muratori.

Saverio Muratori’s fundamental role in the formation of Caniggia’s thinking is fully dealt with in another part of this publication.

Our intention here is to develop certain considerations, already disclosed at the Cernobbio convention in July 2002[1], about Caniggia’s heritage from didactic experiments conducted by the Roman School of Architecture between the two wars, based on history’s new centrality in built environment interpretation and design and the architectural swing-back, foreshadowing “redesign”, tooled by planners and implemented by the built environment’s forming processes, through which the notion of organism is actually transmitted as an “integrated, self-sufficient correlation of complementary notions with a unitary aim”.[2]

A great deal has been written, especially during the post-war period but also in recent times, about the conservative standpoints of the original Roman School of Architecture, generally considered “academic” in its meaning of pedantic submission to traditional design forms and rules: didactics not abreast of rapidly changing times and design contrary to the spirit of modernism, equivocally identified as avant-garde for some time.

In fact Giovannoni, Fasolo and Milani, innovatively followed by Muratori and Caniggia, were perfectly conscious of conditions induced by modernity yet, like all classic thinker, they interpreted avant-gardism as a loss of rules and fragmentation of the basic unity of knowledge, clearly acknowledging its compounding of problems. In architecture, these fragmentations coincided with the irrational destruction of established values with intellectualistic and, therefore, unruly abstract experimentation.

They were fully aware of the true conditions of the modern crisis and, also, how it was impossible to repeat the archaic unity of things that had enabled the historic continuity of civil experiences, building cycles and decadence of forms. They also knew that the world required new answers to up-and-coming, complex problems. Yet they did not agree – and this is where they differ from the Modern Movement’s pioneers and their followers – on the accepted meaning of the crisis, faithful adaptation to new myths and noting of the desegregation irreversibility of every shared and authentic language. Not to mention every style. However, in the wake of major reformers, they did not surrender to the apparent evidence of objects by interpreting the built environment not as it appears but, according to their own design ethics, making interpretation converge with a transformation hypothesis that gave meaning to the built environment, unifying in the “thought which became architecture” the conscience of countless phenomena which otherwise appear as simple, dispersed fragments.

Giovannoni’s intuitions, Muratori’s major territorial visions and Caniggia’s interpretations of the organic transformation of basic building into specialized building are interpretations that not only imply design but are, themselves, design from many standpoints.

In Caniggia’s thought, the interpretation of modern succession (of critical conditions resulting from bewilderment vis-à-vis repeated, extended area exchanges, from the internationalisation of critical design tools, from the generalized serialization of forms and from the arising of new production modes) joined a current of thought originating from the criticism of contradictions arising from the radical split between reading interpretation and construction generated by the loss of the synthetic, unitary idea of organism. Just in this radical split they recognised the formation of various tendencies in international modernity, starting from the beginning of the century.

Fully comprehending how modern architecture cannot be traced back to a single corpus of design theories and tools, synthetically individuated through a presumed common language, Giovannoni raised the issue as far back as the Thirties. He opposed militant propaganda who tended to debase an unitary idea of the Modern Movement by sustaining the existence of numerous, contradictory forms of modernity, individuating the topic around which opposite design principles revolved in the discord between analytical technical and intuitive artistic components and in its direct upshot, individuated by the unsystematic relationship between structure (in the sense of static-structural system) and architectural form. The parallel transformation process of its technique and aesthetical principles, which enabled continuous exchanges among complementary disciplines, ended during the 19th century when the thread of stylistic continuity was broken between building and form and the two terms “seemed to belong to an organism that had lost its physiological balance”[3].

Giovannoni accused the split between architectural “imagination”, eclectic building and, above all, modernism at the beginning of the century for the fall of the “principle of truth” that has always been, during the course of history, one of the ethical rules that architects were called to obey, as proven by modern Roman architecture, unsupportive of innovative trends such as liberty that proposed such an indirect relationship between interpretation and typological character of architectural organisms as to leave the study of façades to other disciplines as visual arts and industrial design. Giovannoni did not reduce the “principle of truth” to a simple cause-effect relationship between static-structural solutions and spatial-pattern upshots, by introducing the implicit relational – and not mechanical – notion that averages form and building and which Caniggia then developed out rightly in his exposition on “direct and indirect” interpretation forms of architectural organisms, specially in his second volume on basic building design[4]. To oppose the simplifications of positivist trends, Giovannoni provided an implicit definition of the notion of interpretation that actually seems to foreshadow Caniggia’s thoughts, establishing the principle that the foundation supporting architectural composition must not only have an “actual structural basis” as building rules provide precious means of expression in simple cases and, anyway, do not suffice in the most exacting applications. Structural nature must arise as a component or “general compositional sentiment” in the formation of the building’s general character, avoiding solutions that bare its body or even “display its skeleton”.

In fact, Giovannoni individuated the splitting of original design unity into various, specialized aspects of modern architectural thought by thinking about form and admitting how – in certain research series – indirect interpretability prevailed over direct interpretability of structural organisms,

The positivist line of thought was individuated in the sequence that originates in Schopenhauer’s assertions in Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung on the disagreement between architectural weight and rigidity and that was developed with Viollet le Duc’s constructivist theories expounded in Entretiens sur l’Architecture and with Pugin’s assertions (considered, amongst other things, to disclose functionalist architectural interpretation) and ended with queries raised by new building experiments and by new materials answered by Modern Movement theoreticians, especially Le Corbusier in Vers une Architecture nouvelle, in aesthetical machinery and manufacturing terms.

Alongside this line of thought and in direct opposition to its apparent productive pragmatism, Giovannoni individuated a second set of theories that privilege (dimensional, geometric and chromatic) aesthetic rules actually linked more to physiology than to reason, an expected design principle. This line of thought was rooted in ancient theoreticians, who seemed to find new justifications in abstract art, true to the positivist meaning of architectural work, without any contemporary critic revealing its contradictions. Even though inexplicably Giovannoni – who had individuated in August Tiersch’s proportional theory the link between ancient treatises and modern design, does not exemplify the results of this different component of modernity in architectural practice – he evidently alludes to works such as Le Corbusier’s Villa Stein, where the town plan appears, free from any structuring reasoning, to exorcise the arbitrary nature of its façade composition by stating its hidden Muthesian derivation from Anglo Saxon picturesque tradition.

The start of modern interpretation of the expressionist series, in opposition to “formal and objective” aesthetics based on geometric rules – the third group of theories that was also latent in ancient and Renaissance treatises – was grasped by Giovannoni, especially in studies on the use of psychology in interpreting Wölfflin’s artistic work, while a fourth group of theories was acknowledged in the work of those who derived architectural forms from the environment, intended as much to be an historic context as the nature of the place, clearly raising the issue – which lasted right throughout the second half of the 20th century, especially during the seventies and eighties – of its relationship with area references, often simplified in the internationalism-localism combination.

This interpretation of modern architecture is evidently the disruption of shared, original organic totality and Muratori’s interpretation of modern succession – as it was expounded during the period that coincides with the first critical elaboration phase of Caniggia’s thought – in his first post-war writings and in lessons imparted at the Roman Faculty of Architecture at the end of the fifties, retrieved and published by G. Cataldi and G. Marinucci in 1990[5].

Yet, at the same time, Giovannoni admitted how the theoretical innovations that characterized the Modern Movement, albeit with unexpected results, were an attempt to overcome the late 19th century eclectic drift in an endeavour to rebuild a new full design form.

Antinomy between modernist theories and the structural procedure that Giovannoni acknowledged, amongst other things, in manifest rational architecture: in fact, he does not out rightly refuse rationalism “that sticks to the principle of necessity and sufficiency” but the “unreasonable” rationalism that ends up by splitting design issues into structural “exaggeration” on the one hand and functional exaggeration on the other; the two sides end up by sticking to the same formal arbitrary principles of ecleticism, including in design unity the remaining spontaneous component that enables art to be spoken about as “presumptive intuition” or “an early form of knowledge”[6].

The same fragmentation of other modernistic trends hid behind recent developments of rationalism: the technically exalted truth principle was actually contradicted by the lack of a general shared order and of a discipline that freed design from the changeability of fashions and from extemporary invention.

Right from initial syntheses during the forties, Muratori’s thought seems to extensively resume and develop certain issues raised by Giovannoni, not only by basically acknowledging lacerations in modern succession and including modernism among eclecticisms (environmental aestheticism) that had lost the order governing the unitary formation of architectural organisms but also reconsidering, more generally, the linguistic fragmentation that preceded the first world war as the origin of the crisis in modern language. Despite its moderation as compared to the excesses of 19th century eclecticism, this phase was an ambiguous passage in the history of architecture; disbelieving linguistic unity, it ended up by being an “anti-stylistic” period”[7].

Contrary to superficial, misinformed historiography that dichotomously separated academics from innovators, Giovannoni criticized modern and, therefore, perfectly updated, fertile internationalism, consciously included in the contemporary debate. In other words, it is not a question “on the one hand of persons ignorant of the European cultural picture”, as Caniggia observed – nor of informed participants. If anything, the apparent independence of the former from diatopic architectural developments and the intentional upshot of their attention to the relative autochthony of experiences and of their continual reference to local participation compelling continuous critical choice to exclude modes and behaviours considered out of character with the place itself, to prefer outside experience and to assume facets in character with the Roman built environment”[8].

In keeping with this critical series developed between the two wars, Caniggia also accepted the basic historic need for the Modern Movement, admitting how it strove to bridge – despite contradicting aforementioned specializations – the gap between the interpretable form of buildings and aggregates and their relative building and fabric types: especially in basic building. The imitation of interpretability originating from specialized 19th century building was sometimes successfully overcome by part of modern architecture’s endeavour to swing-back to a comprehensible relationship between building (orientation of building parts, ceiling texture and layout of bearing walls) and external interpretability (hierarchization of apertures and expression of dwelling units in shells).

According to critical intuition that was already latent in Giovannoni’s thought, the Modern Movement was mainly accused of not having taken forming processes into account and, therefore, of professing aestheticism and being individualistic. However, these processes continued to operate also in wider spread modern architecture, in a sort of area inertia that could not be completely eliminated. As in the case of Oud’s row houses in Kiefhoek, where façade walls are evidently not bearing and strip aperture seems to be rooted in the local language and in the flexible wooden origins of the Dutch area – despite its out-of-character flat-roof solution – or in the case of Fisker’s block in Copenhagen where obsessive holing seriality, indifferent to the dimension of underlying rooms, is made to originate from its wooden trellis construction and continual windows, even though the corner solution right around, more pertinent to masonry areas, seems to be out of character with local tradition.

- UPDATING THE NOTION OF ORGANISM

The innovativeness of the line of thought leading from the Roman School, which formed between the two wars, to Caniggia, can be assessed by comparing it to surrounding conditions in the context of the international debate on architectural design tools. If related to European schools’ contemporary interpretation of disciplines such as the History of Architecture or Restoration, for instance, it is worth mentioning the Roman School’s great effort to renew them by restoring monuments, not just as a constituent part of architects’ culture but also as a way of extracting linguistic rules from the series of texts handed down by history.

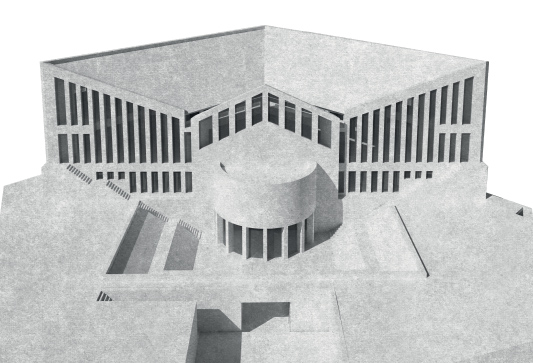

Caniggia developed, innovated and systematized this heritage by introducing the issue of not only comprehending cultured monumental language but also basic building “dialect” to such an extent that he almost founded a new discipline – which becomes increasingly valuable the more we consider the cultural climate in which his didactic and design experiments were conducted – countered, with rare major exceptions, by confused reinterpretations of the past, intended as a morphological repertory for looting, or spent revivals of the Modern Movement’s principles[9].

In order to get to the bottom of this discipline, consider the founding role played by the teaching of history, continually updated by Gustavo Giovannoni and then Vincenzo Fasolo at the Roman School, during the pre-war period. In fact, this teaching was imparted not only though institutional courses on the History of Architecture but also through a real “didactic organism” necessarily pooled with courses such as Stylistic and Structural features of Monuments, imparted for many years by Guglielmo De Angelis D’Ossat as from 1937, basically true to Gustavo Giovannoni’s views and in the conviction that restoration, like all architectural operations, possesses inevitable critical and, all round, design material. This didactic organism was fundamentally boosted by Monumental Restoration teaching, imparted during the first year of the Regia Scuola di Architettura in via Ripetta in 1920-21, before it became a university faculty, by Sebastiano Locati, a teacher who played a brief, yet significant, role in linking up with Lombard research and the antecedents of Boito, who had taught him. Trained at the Brera Academy and then at the Milan Polytechnic School and an authority on Roman monuments’ organic features by directly surveying buildings, Locati proposed restoration based on rules analogically deducible from a stylistic comparison between synchronic works: restoration considered by his technical and artistic training as the synthesis of all architectural disciplines, by interpreting planner roles similarly to Giovannoni. This teaching was then taken over by Giovannoni himself for twenty years until he stopped lecturing in 1943, testifying to the discipline’s founding role in the Roman school’s more general didactic design context.

For Giovannoni, didactic restoration of the work’s original organicity by interpreting typical transformations was actually a tool not only oriented towards restoration but, more generally, towards comprehending the forming processes of architectural organisms. When faced with the problem of restoring a work of architecture, Giovannoni intentionally proposed – moving away from Viollet le Duc-style back-swings and with a surprising assertion of principle that, however, was perfectly consistent with his theoretical assumptions – that works could never actually be completely restored (note the affinity with Caniggia’s thoughts).

Therefore, it is clear how restoration was not just intended as study and safeguarding of the document’s historic and artistic aspects but also as a purely design operation which, like all design, is critical modification of the built environment and also restoration of the qualities of the organism intended, Caniggian style, as individuated type.

In fact, Giovannoni realised the specificity of the method used by architects to research other disciplines and how architects, “when they apply methods, fit for other arts, to architecture, also become amateurs and often presumptuous.”[10] With this background, history could not be considered as a tool of knowledge with independent aims but ended up by foreshadowing “operational history” that was forcefully proposed by the Muratorian school during the post-war period and whose capacity, especially in the field of the recovery, conservation and safeguarding of historic fabrics, restoration culture – as Gaetano Miarelli courageously called it – “was unknown or incomprehensible to it, let alone exploitable by it.”[11]

Lastly, drawing disciplines were to assume a vital function in the teaching of the history of architecture at the Roman Faculty[12]. In fact, drawing became not merely a communications and graphic transmission tool, as in schools for applied engineering, but above all a means of research and knowledge, linking history’s role to that of design[13].

As a result, according to a thesis that Giovannoni had developed some time back, architectural research was supposed to be “unitarian”, i.e. examining the phenomena that structurally and aesthetically combine unitarily to form the organism, and in terms of practical spatial and financial requirements, of external expressions and of its relationship with civilization and social conditions”[14].

The issue of teaching unity as essential to the organic synthesis expressed by design had already been raised by Giovannoni in 1907 with his proposal of the “complete architect”, who would have been trained though coordinated fields of study, each oriented towards “complete artistic training”: technical training “comparable, albeit in a narrower field, to that of civil engineers; independent study training produced by general culture “that could only be provided by a university”, and in-depth knowledge of architectural and art history”[15]. An idea resumed by Giovannoni on various occasions with his “complete architect” proposal, judging that – amongst advocates of “architecture as merely a branch of building science” and of “architecture as always, and above all, art with a capital A, which cannot be compressed by too many other notions” – architects have to be artistic experts who have acquired specific qualities not through “independent notions” thrown together but as expressions of unique thought, unique energy”[16].

In fact, the albeit remote origins of the Regia Scuola di Architettura di Roma paved the way for organic synthesis among disciplines, starting from the proposal put forward by the Commissione dell’Associazione Artistica to architectural scholars, also joined by Giovannoni, Magni and Milani, which envisaged teaching with four groups of disciplines unitarily converging: design based on architectural composition, academic drawing and decoration, science borrowed from polytechnic school teaching and history including restoration[17].

The origin and consequence of the new didactic method was the notion itself of organism around which Composition courses revolved. In 1931, at his Architectural Course, Giovannoni wrote that architectural elements should compose “organisms that together can be considered structural in that they have to be practical, stable and distributive -consisting as they do of numerous elementary spaces interconnected through a determinate function – and aesthetic on account of the type of beauty adapted to the theme and to the environment that they have to adopt both outwardly and inwardly.

This notion of organism also formed the basis for technical teaching as in certain engineering school disciplines. In this sense, Giovan Battista Milani played a major role in studying the stability of buildings. In fact Milani, addressing the purely technical issue of design in his fundamental L’ossatura muraria (Turin, 1920), not only felt how it had to be referred to a more general rule of unitary need among parts of the building but referred to interpretations of both ancient and modern architectural organisms, which were the texts in which the etymons and rules of contemporary language had to be acknowledged.

During the post-war period, Vincenzo Fasolo continued teaching the History of Architecture based on the notion of organism and oriented towards design without, however, substantially updating the method and, on the contrary, acknowledging the contribution of 19th century French positivism treatises and, in particular, Choisy, Gustavo Giovannoni and Giovan Battista Milani, who clearly identified the relationship between structure and form. Yet Fasolo also stressed building interpretation, whose actual structural conception was not simply the way of materialising an architectural invention but formed an integral part of “expression” and the “utilitarian issue” solution. This interpretation did not simply coincide with the analysis of the visible part of the building yet, by resuming Muratorian school intuition, it also concerned its invisible part to the extent that – as ancient principles still applied to new artistic expressions – Fasolo suggested continuing decoration even in concealed building parts in order to “sense their existence even when they are out of sight” [18].

In his Guida metodica per lo studio della Storia dell’Architettura, pointing out the specificities of his teaching method as compared to others, he explains that the treatise addresses subjects “for our teaching aims and expands on building frames”. In fact, we have to realise how these buildings were constructed in various building materials, how spatial conquests were made and how stability relationships between parts of buildings materialised. In other words, it is a question of analysing “the organisms” of buildings.[19]

At a critical stage for design disciplines and the role of architects, for Fasolo, works of architecture still manifest the degree of civilization achieved by a civil neighbourhood during a certain period in history.[20] Fasolo’s interpretation of history focused on design just as Gianfranco Caniggia’s interpretation of the built environment was design: interpretation as the dialectic synthesis between the subject’s intentions and capacity and the object’s attitudes[21]. The difference between “restoration”, as active reinterpretation of the lesson imparted by the monument, discovered by Caniggia at History of architecture courses during the early fifties[22] and “redesign”, as reconstruction of the forming process of buildings and building fabrics, is basically due to the new onus placed on the critical aspect of built environment interpretation.

During the fifties, some of Fasolo’s proposals on the static and spatial collaboration of components in forming architectural organisms – partially disclosed by Milani’s previous systematisation of matter – seemed to foreshadow thoughts processed by the Muratorian and Caniggian schools: see for instance the systematisation of matter proposed by G. Cataldi at the end of the seventies[23].

Fasolo evolutionary distinguished two major categories to which the same number of spatial systems corresponds: systems working out of gravity, without forcing, on continuous or discontinuous support (beam supported systems, mainly pertaining to ancient Greek, Egyptian and Persian civilizations) whose repeatability and seriality are implicitly individuated; systems working vertically and horizontally, and therefore, forcing, on continuous or discontinuous support (vaulted structures mainly pertaining to ancient Mesopotamian, Etrurian and Roman civilizations) consisting of more organic elements that differ in their structural duty, foreshadowing Caniggia’s definition of organicity as a “feature of aggregation consisting of elements that differ in their peculiar position and form and that are, therefore, unrepeatable and not interchangeable, just as each constituent element can be placed in one single position and in one single role within the aggregation, and has its own form and function, opposable and complementary to the roles, positions, forms and functions of other constituent elements.[24]”

The static-structural system intervenes, unitarily with other components, also in determining various types of spatial systems: see, for instance, Fasolo’s distinction between central organisms with a heavy or elastic roof and central domed organisms, where the static-structural component does not so much erect the building as compose a linguistic and integral part of the type individuated in the design, together with its distributive and spatial system, whose nature depends on materials and their workmanship.

Caniggia openly refers to Fasolo’s renowned “nine Doric rows” leading to structural interpretation of the classic code; the nine rows (and eight underlying areas) indicate the origin of cultured language transmitted to monuments in subsequent eras by spontaneous building vernacular.[25]

If it is true that Caniggia’s demonstration of the link between profound linguistic etymons and the structural grounds that helped to form codes was probably inherited from Fasolo, albeit more intuitively than antecedent wise, it is worth mentioning – also to avoid debasing inexistent mechanical derivations – how the fundamental analysis of the organic (logical and process) relationship between fabric and building does not appear in Fasolo’s treatises and, more generally, in the Roman school’s historic interpretations before Caniggia’s thought.

Palazzo formation interpreted by Fasolo in subsequent transformations, starting from noblemen’s palaces, is still linked, for instance, to the traditional interpretation of Italian historiography whose version he provided in the second volume of Le forme architettoniche, edited together with Giovan Battista Milani[26]. And if, in Caniggia’s teaching, the interpretation of walls overlooking an inner courtyard – already proposed by Fasolo as the building’s real main façade – basically reappeared, Caniggia’s individuations have a radically different, innovative meaning: they are based on the assumption that palaces have to be interpreted as fabric specialization (“from the fabric and in the fabric”) and as an aggregate “overturned” in its routes inside the building, re-proposing all urban hierarchization features and ending up by explaining the substantial continuity of various building scales and demonstrating built environment data that appeared in Fasolo’s expositions as simple observations.

- REDESIGN

Despite lacking in the systematic nature that characterized Muratori’s post-war teaching, the method of comprehending the built environment through its swing-back interpretation, analysing relationships essential to the formation of structures collaborating to form the organism, shaped the teaching of the Scuola superiore di architettura di Roma right from its foundation, especially the teaching of disciplines that revolved more directly around the History of Architecture course.

In the ensuing debate, application of the decree of 31st October 1919 establishing the Regia Scuola superiore di Architettura, Vincenzo Fasolo went as far as proposing – in view of the new School’s opening months– that students’ entire training should be based exclusively on interpretation of the built environment, especially its specialized and monumental part and that the first three years should be entirely dedicated to studying the formation and transformation of architectural organisms to synthesize all the School’s teachings, which were to become real structures collaborating in the general didactic organism and unified by history. In fact, the study of the form of organisms had to combine the following curriculum: scientific-technical subjects, comprising analysis of the static arrangements of various structural systems; “general culture” subjects, which were supposed to explain the remote cause of transformations putting them into a more general – and not purely architectural – light; artistic subjects to make students familiar with the meaning of sets of decorations and, lastly, more compositional subjects which were to be imparted through stencils and exercises on “actual theme application” that was not supposed to repeat repertories but to “personalize” them. Fasolo maintained that they all foreshadowed modern design, which was studied during the last two years of the course and that was, anyway, the upshot of a forming process whose need had to be proven by historic disciplines. It is not hard to perceive this proposal that, despite arousing heated debates, met with a large following: the roots of the design-interpretation combination that then basically shaped Roman design didactics.

In Fasolo’s justifying of his proposal, the centrality of the notion of type is also explicit. In fact, the study of past organisms served less to traditionally divulge the history of architecture than to become familiar with how certain building forms were historically “necessary”, limited in numbers and could be updated to satisfy modern-day needs: “in architecture, as in life, invention is very restricted”[27]. Despite the aggressive extremism with which Fasolo put forward his proposal, he only met with the partial opposition of colleagues and Arnaldo Foschini, who held the course on Composition, raised reservations more of a practical nature than on principle.

The peculiarity of Fasolo’s History of Architecture teaching actually lay in his attempt to transmit to students his observation of architectural organisms as the result and unification of collaborating structures. His lessons were conducted by graphically reconstructing detailed elements of the building before structurally and spatially linking them until they represented the whole organism, almost as though the teacher’s task was to design a new organism starting from the tools of a certain civil phase in the presence of students, aided by legendary graphic capacity.

Therefore, reconstruction of the architectural work’s features through surveys also became interpretation or retracing the monument’s forming process with measuring and dimensional ratio tools, on which building type study conferred a meaning and content. Giovannoni deliberately concluded his inaugural speech at the new School of Architecture by praising the function of surveys as a didactic tool oriented towards design, whose “main experimental aid will be the practical survey of local monuments, be they noble or humble, in order to comprehend their type and meaning by dissecting them, back tracing the path followed by the architect and planners who composed the organism and shaped its elements: starting from plans and their structural layouts (that only those who do not understand architectural conception can consider superfluous) as far as designs and decorations on their facing.”[28]

Yet redesign practice also has a remote origin that does not necessarily coincide with that of historic studies: it is not only professionally and didactically customary with Roman monuments but also with restoration’s particular guidance, provided by study tradition and interventions on ancient moments (just think of the numerous antecedents exemplified and compounded by Piranesi), as the main didactic tool. When modern design procedure saw analytical-technical components progressively breaking away from intuitive-artistic components, the general knowledge essential to architects’ training, monumental study, became a discipline that – professional aims aside – fulfilled its fundamental educational task, not only with a unitary view of the design of various building components but also to synthesize forming process, which presided over architectural composition and were individuated in the substantial continuity between interpretation and design. Architects’ interpretation is never inert verification and reading up on the built environment but, even more than a traditional driving force, it is design that involves their critical conscience and selective and interpretative capacity, according to a method that has continued at the Roman School of Architecture virtually to date. Therefore, the monument’s history and development stages had to be “swing-back tested”. More generally speaking, restoration was intended as a critical, fundamentally design, act that restored the work and not the series of fragments handed down by history. It studied how the element testified to a structure of relations that originally linked it to other indispensable elements. And this structure – like, to a greater degree, systems and inherited organisms – can only be recognisable by comparing it to other structures and similar systems.

This modern monumental restoration[29] conception also propitiated the formation of a new connotation of the notion of type as a set of historically individuated laws and rules that determine a typical relationship among elements, structures and systems combining to form the architectural organism.

From many standpoints, redesign proposed at Caniggia’s courses (in Genoa, Florence and Rome) inherited, updated and upgraded the foregoing: history as swing-back processes still under way both on building and on building-aggregate scales; restoration as rediscovery of the built environment’s charter laws not so much of monuments as basic building aggregates, apart from compensation for damages caused by a culture out of character with the inherited features of the town and territory. Restoration is not, therefore, just conservation of the artistic and documentary value of individual building works or aggregative organisms: it is recouping their value as organisms reconsidering the relationship between “authentic”, “false” and “integration” and legitimising the reconstruction of an albeit unauthentic text that, like the copy of a manuscript, certainly does not retain its original, but its literary, value.

Where monuments were not simple ruins but “live, complete organisms” it is worth remembering how Giovannoni insisted on restoration “that restores their harmony”.[30]

Therefore, historic cities became texts that safeguarded linguistic origins and in which daily vernacular laws had to be recognised, tracing back “concealed architecture” and grasping process symptoms that could still enable design in character with the inherited building culture[31].

Filtered through fundamental experiments conducted at courses held by Muratori in Rome as from the 1961-62 academic year on redesign of historic fabrics such as Tor di Nona but also on contemporary fabrics like Centocelle, experiences proposed by Caniggia to students tended to “asymptotically” approach, through successive approximations, the real built environment process gradually conquered by its critical process through interpretation.

Interpretation that gave rise to a design method which, directly derived from the built environment, avoided the shortcomings and risks of the ideology that largely contributed to the disaster of modern architectural theories.

Giovannoni had already schematically raised this issue by acknowledging how theory ends up by having independent grounds and upshots from design: “Theory runs its own course, tracing its own rigid forms and expounding its own unilateral cocooned philosophy; reality often goes its own way but this net difference in thought and process does not lead to formal dissention. On the contrary, a tacit agreement seems to have been established to enable artists’ freedom of action, elegantly feigning in order to make them humbly accept the lofty principles with which theory intends to guide them. The laborious evolution of art requires a layer of dead leaves to conceal and protect new germination.”[32] This observation concerned the issue of interpreting past works, for which they continued to use (arousing renewed criticism of Muratori and Caniggia) theoretical art history tools, without taking into due account their features as organisms (plans, structural reasons).

In fact Giovannoni, unlike Caniggia who based himself on Muratori’s systematisation of matter assumptions, arrived at the notion of aggregative organism through successive approximation, progressively abandoning wide sweeping theories. If Giovannoni’s initial spacing-out theory proposed an abstract idea of fabric, in time it evolved by taking into account the features of the environment surrounding the moment and its historic and artistic value: if properly designed, new spatial and route-hierarchization brought about by “systematisation” could lead to updating the urban aggregate, according to new polarizations. In other words, albeit far-removed from Caniggia’s procedure and contemporary positions also in northern European modernism, that isolated historic buildings, even dwellings, from their pertinent lot. Giovannoni progressively approached a building aggregate idea as individuation of a more general typical law, i.e. of fabrics. In addressing the brand new “cinematic city”, Giovannoni sensed the latent developments of this notion on an urban scale, as an alternative to town planners’ widespread belief that they could split towns into single-functional, specialized parts and separate the zoning principle from the idea of urban form connected to building design: “tracing road sections without knowing whence they could lead or laying tramway lines or metropolitan undergrounds without taking their building function into account expresses empiricism as opposed to rational conception”[33].

Yet, affinities and derivations aside, also in the light of subsequent studies, sources and antecedents, Caniggia’s research on the formation of fabrics and their transformations and specializations must be acknowledged as being surprisingly original and unequalled in Italian schools of architecture. Differences in method with parallel Italian typological research have been fully investigated. However, analogies were recently found with studies conducted by geographers who, when Caniggia was commencing his research, felt the need to extensively renew territorial surveying tools and start investigating urban morphological issues. In England, the German geographer M.R.G.Conzen, a lecturer on Human Geography at Newcastle upon Tyne University, experimented on the town of Alnwick a town plan analysis method, based on the process of lotting and then aggregating into blocks updated by a streets system. Conzen proposed an interpretation method oriented towards restoring a forming process, apparently unknown to Caniggia[34] and based on the general hypothetical behaviour of medieval urban tissues, analogous to Caniggia’s thought on progressive building-type updating and contemporary permanence of systems and fabric[35]. Yet Caniggia’s research also differed from these studies on account of his synthesis on different scales, whose substantial continuity was acknowledged, starting from the notion of territory, which also originated from initial street hierarchization, to building organisms – giving rise to the distinction between basic and specialized building – but also of their unity, through the “cellular nature” of fabrics and typological continuity.

- AESTHETIC SYNTHESIS AND THE NEW NOTION OF STYLE

With the course of events at the Roman School of Architecture between the two wars, the term “expression” meant the architect’s effort to synthesize formal unity, “the end result of architectural conception”[36] in opposition to contemporary designers’ individualistic versions but also to research methods used in architectural historiography at the time which, under the influence of Adolfo Venturi’s criticism professing aestheticism, tended to privilege architects’ individuality and the exceptionality of works.

Despite superficial and, anyway, far-removed affinities with the 19th century French school, the restoration didactic issue ended up by involving the definition itself of “style”, intended as much a built-environment interpretation tool as a design tool. The restoration issue was raised innovatively not to interpret style, intended as choice of individual expression and the artist’s visible peculiarities, but to historically comprehend the organism’s essential features to the extent that the “real form” of the monument could not paradoxically coincide with its original form.

The new onus placed on structural features synthetically individuating the system of building organisms is indicative of breaking away from art historians’ methods and definitions: instead of the accepted meaning of the term “style” as a language used in works (in architecture as in painting or sculpture) and traced in ornaments, particulars and details, its definition implicitly ended up by acquiring, also through De Angelis D’Ossat’s teaching in Caratteri stilistici dei monumenti, new connotations and meanings, foreshadowing Caniggia’s systematisation.

As far back as 1920 Giovannoni wrote, “Style is not architectural crystallization but a series of stages in a continual flow, a series of groups of forms, whose temporal and local evolution often proceeds irregularly with adaptations and evolutions; style is not a sporadic plant that ‘germinates like spelt grain’. It only germinates with special soil conditions for various permanent or changing, material and historic, ethnographic and social reasons and it is essential to know these causes in order to learn its artistic and structural characteristics and to get its gist and meaning.”[37]

This different conception of style – linked to a latent notion of process and the synthetic idea of structure that binds collaborating parts, expressed and interpretable through a language common to civil environs and pertinent to a determinate historic phase – induced the design of ancient organisms, their restoration and interpretation in a new form: bare, essential and often stripped of details, individually linking the design and interpretation of ancient works to Roman late twenties and early thirties modernist architecture, in which modernity appears as simplification, updating and stripping of inherited organisms. Therefore, this combination of interpretation and design in one single graphic gesture seems to illustrate how the splitting of architecture into disciplines as a didactic contrivance is evident from students’ drawings at Fasolo’s courses on History and architectural styles during the thirties: bare assembly sketches, mass-produced drawings and building frames simplified in order to recognise internal organic relationships, where the “patterns” of basilicas and ancient thermal baths alternate with the “visions” of Greek and Roman architectures.

Saverio Muratori had already picked up the new meaning of the term “style” during the post-war period. Contrary to its generally accepted definition, in 1944 Muratori started re-proposing an accepted meaning, distilled from pre-war experiences, of the term as the unifying rule that presides over action, sensing its bond, which was subsequently developed with the notion of organism and organicity: compositions (reference to contemporary architecture is evident) where elements aggregate without unifying are not stylistic whereas “architectures that explicitly express their structure, i.e. their structural energy, influence us by introducing us to action organicity, stress coordination and an attitude on which style is based”[38].

Even more so today, this new definition seems to be the most evident upshot of a continually updated, profound, ancient heritage, which was handed down to us through Roman didactics during the first half of the past century and innovated by Muratori and his school: in opposition to style intended as “manner, peculiar egocentric form of a certain personality, school, nation or time and, worse still, academy or prearranged stylistic formulary…”[39]. Therefore, style became “absolute reality, recognisable in the collaboration, articulation and synthesis among individual parts, foreshadowing the unity-distinction principle that was then developed in Architettura e civiltà in crisi.

These brief notes on his relationship with modern Roman tradition between the two wars will perhaps help to explain how according to Caniggia – who was the most innovative and, at the same time, faithful interpreter of that universe of ideas and thought – the multiple built-environment forms washed up by history could not simply be classified and scientifically processed as in the series of typological studies generated by Giulio Carlo Argan’s analysis.

According to pre-modern principles, Caniggia sensed how it was necessary to extract hidden, deeper meanings from objects: the world inhabited by man, houses as monuments, thus became not just simple construction but textes and designer-architects had to be capable of interpreting the message conveyed by the text, and also of deciphering not only what the built environment appeared to be but how it should be.

Therefore, in this, Caniggia seems to have inherited, and transmitted, the Roman school’s deeper and more authentic teaching. With his capacity to grasp what was individual and to recognise its vital belonging to the more general, living anthropic environment, he ended up by restoring it for us as a constituent and inseparable part of a shared heritage.

[1] G. Strappa, L’eredità progettuale di Gianfranco Caniggia, in C.D’Amato, G.Strappa (b), Gianfranco Caniggia. Dalla lettura di Como all’interpretazione tipologica della città, proceeds of the international convention held in Cernobbio on 5th July 2002, Bari 2003.

[2] G.Caniggia, G.L.Maffei, Composizione architettonica e tipologia edilizia 1. Lettura dell’edilizia di base, Venice 1979, page 47.

[3] G.Giovannoni, Il momento attuale dell’architettura, in G.Giovannoni, Architetture di pensiero e pensieri sull’architettura, Roma 1945, page 238.

[4] G.Caniggia, G.L.Maffei, Composizione architettonica e tipologia edilizia 1. …cit.

[5] S.Muratori, Da Schinkel ad Asplund. Lezioni di architettura moderna. 1959-1960, published by G.Cataldi and G.Marinucci, Firenze 1990.

[6] G.Giovannoni, Il momento attuale… cit., page 274.

[7] The theses that he asserted at his lessons during the fifties are basically disclosed in his works Storia e critica dell’architettura contemporanea (1944) and Saggi di critica e di metodo nello studio dell’architettura (1946), in S.Muratori, Storia e critica dell’architettura contemporanea, Roma 1980, published by G.Marinucci.

[8] G.Caniggia, Permanenze e mutazioni nel tipo edilizio e nei tessuti di Roma (1880-1930) in G.Strappa (by) Tradizione e innovazione nell’architettura di Roma capitale.1870-1930, Roma 1989.

[9] Chronologically, the general study of the relationship between “dialect” as a product of spontaneous conscience and “cultured language” as the product of critical conscience started from Caniggia’s studies on territory, intended as an organism comprehensive of all degrees of anthropic transformation. As part of Saverio Muratori’s teaching, Caniggia held, during the 1965-66 academic year, a course on Surveys – design of territorial structures, which included the study of “deduction and reinterpretation from structures and typical organisms and from individual and environmental processes of typical territorial constants and their application” (Cf. Programma dei corsi e attività di Istituto, Istituto di Metodologia architettonica dell’Università di Roma, Facoltà di Architettura, Roma 1965-66.)

[10] G.Giovannoni, Prolusione inaugurale della nuova Scuola superiore di Architettura di Roma, read on 18th December 1920 and published in G.Giovannoni, Questioni di architettura, Roma 1929.

[11] G.Miarelli Mariani, L’insegnamento del restauro. Il quadro d’insieme, in V. Franchetti Pardo (by), La Facoltà di Architettura dell’Università “La Sapienza” dalle origini al 2000. Discipline, docenti, studenti, Roma 2001.

[12] On the history of the Roman Faculty of Architecture, see not only the volume by V. Franchetti Pardo, La Regia Scuola di Architettura di Roma, Roma 1932 but also L.Vagnetti and G. Dell’Osteria (by), La Facoltà di Architettura di Roma nel suo trentacinquesimo anno di vita, Roma 1955. Particular significance in comprehending didactic design lies in Prolusione inaugurale della nuova Scuola Superiore di Architettura, read by Giovannoni on 18th December 1920, and the publication of Discussioni Didattiche (in G.Giovannoni, Questioni di Architettura, Roma 1929), where Giovannoni refers to the design didactics debate held in via Ripetta classrooms in 1920.

[13] This didactic tradition also had a large following in Muratorian and Caniggian schools. Refer to the didactic text used during the first courses at the Faculty of Architecture in Reggio Calabria: R.Bollati, S.Bollati, G.Leonetti, L’organismo architettonico. Metodo grafico di lettura, Firenze 1990.

[14] G.Giovannoni, Prolusione inaugurale…cit., page 33.

[15] See G. Giovannoni, Per le scuole d’Architettura, in «L’Edilizia Moderna» N°12, 1907.

[16] See G. Giovannoni, Gli architetti e gli studi di architettura in Italia, in «Rivista d’Italia», XIX, 1916.

[17] The ensuing didactic system initially kept disciplines laid down nationwide by the Nava law of 1915.

[18] V.Fasolo, Guida metodica per lo studio della Storia dell’Architettura, Roma 1954, page 151.

[19] V.Fasolo, Ibid., chap. IV

[20] V.Fasolo, Ibid., chap. IV

[21] G.Caniggia, G.L.Maffei, Architectural composition and building typology. 2. …cit., page 41

[22] Cf.P.Marconi, Gianfranco Caniggia, architettura e didattica, in C. D’Amato Guerrieri e G.Strappa (by), Gianfranco Caniggia… cit.

[23] See: G.Cataldi, Sistemi statici in architettura, Padova 1979.

[24] G. Caniggia, G.L. Maffei, Architectural composition and building typology.1. …cit., page 71.

[25] G.Caniggia, G.L.Maffei, Architectural composition and building typology.2… cit., page 204

[26] V.Fasolo, Dal Quattrocento al Neoclassicismo, second volume of G.B. Milani’s work, V.Fasolo, Le forme architettoniche, Milano 1934.

[27] Referred to in G.Giovannoni, Discussioni didattiche, in G.Giovannoni, Questioni di architettura, cit., page 57.

[28] G.Giovannoni, Prolusione inaugurale …. cit., page 37.

[29] See: G.Caniggia, Valori e modalità del restauro: valore storico e valore architettonico. Relatività e consumo dell’opposizione dei termini “vero” e “falso”, in G. Caniggia, Ragionamenti di tipologia. Operatività della tipologia processuale in architettura, published by G.L.Maffei, Firenze1997.

[30] G.Giovannoni, I restauri dei monumenti e il recente congresso storico, Roma 1903.

[31] See: G.Caniggia, Progetto e lettura: lettura come ri-costruzione e progetto come ri-progettazione, in G. Caniggia, ragionamenti di tipologia….cit.

[32] G.Giovannoni, Il momento attuale…cit., page 258

[33] In G.Giovannoni, Vecchie città ed edilizia nuova, Torino 1931, page 89.

[34] Caniggia knew and appreciated studies by the Italian geographer Renato Biasiutti who established, in 1938, a series of studies on Italian country-houses published by Leo S. Olschki in Florence.

[35] “In the process, however, the plan and fabric of the town, representing as they do the static investment of past labour and capital, offer great resistance to change. New functions in an old area do not necessarily give rise to new forms. Adaptation rather than replacement of existing fabric is more likely to occur over the greater part of built-up area established in a previous period.” (M.R.G.Conzen, Alnwick, Northumberland. A Study in Town Plan Analysis, London 1969, page 6).

[36] V.Fasolo, Guida metodica …cit., page 121.

[37] G.Giovannoni, Prolusione inaugurale … cit.

[38] S.Muratori, Storia e critica dell’architettura contemporanea. Disegno storico degli sviluppi architettonici attuali, Roma 1944, pubblished by G.Marinucci, Roma 1980.

[39] Ibid., page 192

THE HERITAGE OF THE ROMAN SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND THE CANIGGIA’S NOTION OF ORGANISM

THE HERITAGE OF THE ROMAN SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND THE CANIGGIA’S NOTION OF ORGANISM