PROF. GIUSEPPE STRAPPA

1. IL TERRITORIO COME ORGANISMO

Il territorio è architettura nel suo significato più pieno.

Esso nasce dalla collaborazione tra uomo e natura.

La derivazione etimologica del termine (da terra contrapposto al termine mare) contiene la nozione di luogo abitato, quindi trasformato, costruito e ricostruito dalla mano dell’uomo, contrapposto a quella di luogo inabitato.

Il territorio è anche una grande eredità civile, un patrimonio nel quale sono inscritte le scelte e le trasformazioni operate dalle popolazioni che vi sono vissute. Per questo ogni intervento a questa scala obbliga alla comprensione dei caratteri che possiamo conoscere attraverso la sua forma, sapendo che questa forma è l’esito riconoscibile di un processo in atto.

Essendo il territorio costituito da parti collaboranti, è possibile leggerlo attraverso la nozione di organismo, cioè di insieme di elementi, strutture, sistemi legati da un rapporto (variabile nel tempo) di necessità. E come in ogni organismo è possibile riconoscere nel territorio fasi e cicli storici che ne determinano la formazione, la trasformazione, la frammentazione, la rovina.

Quella di organismo territoriale come luogo abitato costituito di parti collaboranti (percorsi, insediamenti, aree produttive) è, dunque, una nozione complessa che sintetizza i processi analizzati a tutte le scale minori: organismo edilizio, organismo aggregativo, organismo urbano.

Il concetto di territorio deriva dal nesso che lega l’idea di suolo naturale a quella delle trasformazioni artificiali operate dall’uomo nel processo di antropizzazione (trasformazione abitativa e produttiva) del suolo stesso. Noi cogliamo questo processo attraverso momentanei stati di equilibrio che restituiscono un’idea discreta di una sequenza storica che è, invece, flusso continuo di modificazioni e rivolgimenti.

Per questo non è comprensibile il senso storico-processuale di un organismo urbano o di un sistema di percorrenze, se non si colloca la loro formazione all’interno di un rapporto di necessità con l’insieme delle relazioni instaurate nel tempo e nello spazio entro il proprio intorno territoriale. Questa forma del territorio antropizzato non é che l’aspetto visibile di una struttura di relazioni che lega nella nozione di organismo i diversi gradi scalari del costruito e che indicheremo col termine “paesaggio”.

L’organismo territoriale si forma e sviluppa secondo processi differenziati storicamente ed arealmente che possiedono, tuttavia, una loro tipicità, al pari di ogni altro esito del processo antropico. Si può parlare dunque di “tipo territoriale” come insieme dei caratteri fisici processualmente ereditati (patrimonio) comuni ad un intorno storico-geografico, ovvero come insieme delle nozioni e scelte insediative comuni che determinano il complesso delle operazioni di trasformazione del luogo naturale in luogo abitato.

Questa tipicità di comportamento si individua (assume caratteri individuali, unici, irripetibili) nelle trasformazioni reali del suolo determinate nello spazio e nel tempo in funzione di variabili naturali (sistema oro-idrografico, natura geologica del suolo ecc.) e storiche (in relazione, cioè, ad una determinata fase civile). Grazie alla nozione di tipicità è possibile riconoscere il maggiore o minore grado di organicità di un territorio, il quale può essere costituito anche da elementi relativamente autonomi e seriali, che comunque risultano polarizzati da un ordine formativo (dislocativi) più generale, insito nella nozione stessa di organismo.

A somiglianza di quanto avviene nel primo e più elementare dei processi di trasformazione antropica, cioé della materia in materiale, anche l’ultimo e più complesso fenomeno di trasformazione del suolo naturale in suolo abitato é relazionato a scelte operate attraverso un processo di selezione e specializzazione.

– la selezione (da seligere, scegliere) deriva dalla coscienza della differenza tra le cose e dal riconoscimento della loro idoneità ad essere utilizzate e trasformate. L’operazione di selezione è qui intesa come scelta dell’attitudine di un suolo ad essere percorso, ad essere trasformato per uso abitativo o produttivo; potrebbe essere identificata come momento logico nel rapporto di collaborazione tra uomo e natura, quello attraverso il quale vengono valutate le diverse possibilità degli elementi componenti ad essere utilizzati, eventualmente dopo convenienti trasformazioni;

– la specializzazione, è l’attività di restringere e trasformare i caratteri di una cosa per renderla adatta a particolari finalità. Deriva dall’individuazione del rapporto di complementarità e necessità tra le cose. L’operazione di specializzazione è qui intesa come trasformazione di parti di suolo in funzione dei particolari ruoli che devono svolgere all’interno dell’organismo territoriale. Gerarchizzandosi, ad esempio, i percorsi assumono caratteri e qualità diverse in relazione al rapporto che instaurano con l’insieme del territorio. In questo senso la stessa costruzione che, se vista sotto il solo aspetto tettonico può essere considerata trasformazione finalizzata di materia, può qui essere intesa secondo la diversa ottica di modificazione specializzata di una porzione di territorio. La specializzazione può essere identificata come momento tecnico-economico nel processo di antropizzazione del territorio, quello nel quale interviene la finalizzazione individuale, cui succederà una finalizzazione collettiva e una sintesi organica leggibile.

Queste operazioni possono essere lette attraverso una prima, fondamentale diade di termini opposti e complementari composta da “insediamenti” e “percorsi”, legati al moto ed alla sosta in funzione dei bisogni primordiali dell’uomo di proteggersi e alimentarsi.

Da quanto esposto si riconosce al termine “insediamento” il significato di struttura provvisoria o stabile costituita da un insieme di abitazioni relazionate organicamente ad un’area complementare produttiva. Potremmo pensare i primi insediamenti provvisori, come appartenenti alle civiltà dei cacciatori e raccoglitori, seguiti da insediamenti semistanziali, legati alle prime forme di coltivazione o allevamento, dove la nozione di dimora (etimologicamente derivata da de-morari, indugiare, con il senso di permanenza in un luogo) viene associata più stabilmente a quella di area di pertinenza. Il possesso di un’area é dovuto, in origine, all’appropriazione causata dal lavoro che vi veniva svolto con maggiore o minore continuità. E’ da ritenere, a questo riguardo, che le prime, embrionali forme stabili di aree di pertinenza possano essere associate alle trasformazioni antropiche dell’età neolitica, con la diffusione delle coltivazioni, soprattutto cerealicole, dovuta all’esigenza di superare l’instabilità della semplice raccolta sporadica.

Ma la definitiva nozione di associazione di un suolo alle strutture costruite dall’uomo per utilizzarlo, e cioé alle modificazioni antropiche stabili, é da ricercare in quelle fasi storiche e in quelle aree dove la necessità di continua manutenzione del suolo comportava una maggiore consuetudine tra lavoro dell’uomo e area produttiva, come nei territori dove le condizioni per la coltivazioni dovettero essere prodotte artificialmente attraverso sistemi di irrigazione permanenti che comportavano tanto una collaborazione organica tra opere artificiali e suolo naturale quanto una collaborazione organizzativa e specializzazione tra gruppi di lavoro all’interno della comunità agricola.

Questo atto di addomesticamento delle condizioni naturali del suolo, comportando trasformazioni da operare sulla natura semplicemente “incontrata”, implica infatti non solo una scelta insediativa, ma anche la chiara coscienza dell’appartenenza di un suolo alla comunità che lo lavora.

E’ un passaggio culturale che avviene gradualmente attraverso fasi successive di semistanzialità.

Nella conquista della coscienza di identità sociale (il riconoscimento dell’appartenenza al gruppo) collegata alla coscienza di identità territoriale (il riconoscimento di un suolo di pertinenza, più o meno esteso, appartenente al gruppo) consiste l’origine profonda della natura conflittuale delle trasformazioni territoriali. Natura conflittuale che, evidentemente, non é solo,come potremmo oggi dedurre dalla pura osservazione dei fenomeni di frammentazione in corso, un portato della modernità (della formazione delle grandi periferie urbane, dell’aggressione della speculazione edilizia alla condizione di equilibrio che le nostre generazioni avrebbero ereditato) ma conseguenza dello stesso processo formativo della nozione di “pertinenza” .

L’appropriazione dell’area avviene progressivamente col consolidarsi della stabilità della dimora e del rapporto di uso produttivo col suolo: dall’ allevamento brado al pascolo, dall’area di caccia alla riserva, dall’area di raccolta al suolo pubblico (in età storica l’ager publicus romano o il legnatico medievale). A partire da questi processi si svilupperà una partizione delle proprietà pubbliche e private progressivamente associate al costruito quanto più l’area mostrerà sucettibilità insediativa, dando origine al concetto giuridico di proprietà del suolo fondamentale nella dialettica formativa dell’assetto del territorio.

Processi che lasciano, ovviamente, un loro segno visibile sul territorio il qulae, per questa ragione, può essere considerato nel suo aspetto fondamentale di “documento”.

Con il passaggio dall’allevamento brado al pascolo si consolida, infatti, la nozione di recinto associata a quella di area di pertinenza nella doppia funzione di protezione e contenimento: le palizzate del neolitico avevano tanto lo scopo di proteggere quanto di impedire la fuga.

La coltivazione, inizialmente costituita soprattutto da cereali, rappresenta una rivoluzione antropica anche per la necessità di specializzazione dell’abitazione che comporta, dovendosi assicurare, associato allo spazio per la vita domestica, le strutture per la conservazione del raccolto, spesso, nelle aree eurasiatica e nordafricana, nella forma specializzata di silos circolari . Ma il processo di progressiva organicità del territorio matura solo con l’integrazione tra le diverse concause che originano la strutturazione antropica: integrazione non progrediente in modo continuo, anzi, ciclicamente conquistata e riperduta. Delle relazioni tra queste componenti che tendono a stabilire un rapporto organico tra loro, alcune hanno valore fondamentale e la relativa cartografia acquista particolare valore per il progettista:

– quelle connesse alla produzione, e cioé tra insediamenti, attività agricola ed allevamento. Solo quando l’integrazione tra fertilizzazione del suolo e produzione di foraggio per l’allevamento si sviluppa in modo continuo, si può parlare di organismo produttivo associato al territorio. Associazione che diviene complessa, ma ancora processualmente leggibile, con la rivoluzione industriale. La contemporanea cartografia dell’ uso del suolo semplifica e riduce i poli e le aree di attività produttiva. Si veda come esempio la cartografia dell’Istituto Geografico Militare al 50.000 (alla fine del XIX secolo scorso) e al 25.000 (nel XX secolo).

– quelle connesse alla proprietà, e cioé tra suoli pubblici e privati. Solo quando viene stabilito e regolamentato l’uso dei suoli a disposizione della comunità integrati ai fondi privati, si può parlare di organismo fondiario (v. più oltre l’esempio del sistema a centuriatio). La cartografia catastale contemporanea semplifica la rappresentazione del territorio indicando i soli confini di proprietà alle scale 2.000 o 1.000.

Riguardato come organismo il territorio risulta composto, per la definizione generale data, da insiemi di strutture riconoscibili come concorrenti al medesimo fine, ma non autonome: segnatamente, per comprendere il processo formativo dell’organismo territoriale, occorre prendere in esame il sistema viario o sistema delle percorrenze, e quello strettamente correlato degli insediamenti , o sistema insediativo e, in seguito, una volta esaminato l’impianto generale, anche il sistema della partizione delle proprietà del suolo, o sistema fondiario, e il sistema, strettamente correlato, della utilizzazione delle risorse naturali (aree agricole e manifatturiere) o sistema produttivo, che si formano in una fase storicamente più matura del processo di antropizzazione del territorio.

Questi sistemi non svolgono compiti astrattamente di collegamento, di abitazione e produzione, ma sono inscindibilmente collegati, oltre che tra loro, al relativo sistema oro-idrografico da relazioni organiche: un promontorio naturale, separato da due displuvi, costituisce un primo intorno nel quale l’uomo riconosce caratteri specifici, trova un’identità tra gruppo e suolo naturale, così come, in una fase successiva, un bacino idrografico, isolato da confini orografici difficilmente superabili, costituisce la sede di sviluppo di un’area culturale relativamente omogenea per la facilità degli scambi interni che consente. Questi quattro sistemi, benché strettamente integrati, sono inoltre polarizzati per diadi: non solo storicamente, ma anche logicamente percorrenze e insediamenti costituiscono a loro volta sottosistemi di un sistema di maggiore complessità all’interno dell’organismo, così come fondi e strutture produttive possono essere riguardati come formanti un unico sistema unitario.

2. LETTURA E RAPPRESENTAZIONE DEL SISTEMA DELLE PERCORRENZE, DEGLI INSEDIAMENTI, DELLE AREE PRODUTTIVE

La cartografia è una rappresentazione simbolica di una porzione di territorio: come tale essa costituisce il risultato di una riduzione critica delle nozioni dedotte dall’osservazione del territorio stesso, comunicate attraverso forme simboliche.

Il simbolo (dall’indoeuropeo symballein, unire, mettere insieme), a sua volta, esprime in modo sintetico diverse nozioni considerate fondamentali: esso è dunque frutto di una scelta e di una selezione. Per questa ragione lo strumento cartografico (i simboli e la struttura che lega i simboli tra loro) è in diretta relazione con l’idea che l’autore ha espresso, all’interno di un’area culturale e di una determinata fase storica, del territorio che ha rappresentato.

Come è possibile tracciare le linee di un processo di trasformazione del territorio, così è possibile tracciare le linee di un processo di trasformazione degli strumenti cartografici. Il quale testimonia non solo (e non tanto) le mutazioni dei caratteri del territorio stesso, ma, soprattutto, la conoscenza e coscienza che, nelle diverse fasi storiche e nei diversi intorni civili, l’uomo ha avuto dell’ambiente costruito contemporaneo o del passato.

La Tabula Peutingeriana riporta soprattutto una struttura di percorsi; nell’atlante dell’Italia di Giovanni Magini (1620) non compaiono quasi i percorsi di terra; in una moderna carta automobilistica la rete stradale prende il sopravvento sulla rappresentazione degli altri dati osservabili sul territorio; la pianta di una metropolitana, infine, è soprattutto il disegno simbolico ed astratto di una rete, senza rapporto diretto con le dimensioni fisiche delle distanze tra i poli collegati.

Per il progettista, al quale occorre leggere il territorio in modo attivo, avendo come fine l’intervento, è dunque fondamentale estrarre con coerenza le informazioni dalle cartografie disponibili.

Questa coerenza costituisce il legame tra soggetto e oggetto della lettura territoriale: tra quello che il progettista cerca attraverso la rappresentazione cartografica (legata alla propria nozione di territorio ed allo scopo della lettura) e quanto le diverse cartografie possono offrire (legato alla nozione di territorio dell’autore e allo scopo della rappresentazione).

Nel seguito si riporta un criterio di lettura, legato alla nozione di territorio inteso come organismo, attraverso l’esposizione sintetica della nozione di organismo territoriale, della rappresentazione delle sue strutture (fondamentali all’interno della nozione di organismo esposta), degli strumenti operativi che permettono di estrarre dai diversi tipi di cartografia le nozioni ritenute utili.

La rappresentazione della struttura del territorio, individuata attraverso le fasi del suo uso antropico, non può che iniziare dalla lettura dei percorsi: dal modo nel quale essi si formano, si consolidano, si articolano, specializzano e gerarchizzano tra loro in modo collaborante, in rapporto di reciproca necessità secondo relazioni di congruenza e proporzione con gli insediamenti cui fanno capo. Il moto dell’uomo sul suolo, i segni lasciati dagli spostamenti, attraversamenti, migrazioni, precedono, infatti, qualunque altra traccia: qualsiasi struttura legata ad attività lavorativa e stanziamento viene associata ai percorsi, più o meno stabili, che ne permettono l’esistenza.

I percorsi, come ogni dato della realtà costruita, hanno una loro tipicità, sono cioé riconoscibili, nel loro formarsi ed evolversi, caratteri comuni che ne individuano storicamente la fase di appartenenza e, arealmente, la pertinenza ai caratteri naturali del suolo cui sono associati.

Una prima, orientativa distinzione tra percorsi tipici può essere attuata attraverso la gerarchia del compito che svolgono, e quindi attraverso le polarizzazioni che distinguono i tracciati definendone le scale:

percorsi territoriali generati in origine dalle migrazioni ed, in seguito, dai collegamenti tra aree culturali di grande polarizzazione (ne sono esempio contemporaneo i percorsi autostradali) ;

percorsi locali, interni a ciascuna area o tra aree di confine, polarizzati dagli insediamenti e dai nuclei urbani;

percorsi fondiari, collegamenti alla scala delle aree produttive;

percorsi urbani, collegamenti interni alle aree urbane.

Questi percorsi si strutturano, a loro volta, secondo gerarchie che stabiliscono rapporti organici nell’uso del territorio (abbiamo già visto, ad esempio, come nei percorsi urbani é riconoscibile un ruolo processualmente diverso dei percorsi matrice, di impianto edilizio, di collegamento, di ristrutturazione ).

Una seconda distinzione può riguardare la stabilità dei percorsi, la quale é comunque legata alla loro gerarchia e alle fasi formative.

Le più elementari e spontanee vie di comunicazione sono costituite dai cammini originati dal semplice atto del percorrere, e dai sentieri, tracciati in modo sommario dal passaggio frequente di persone e animali, come le mulattiere. E’ interessante notare come i due termini moderni non derivino da etimi impiegati nell’uso del territorio consolidato presso i romani, ma da neologismi del latino tardo, quando le strutture di percorsi consolidate erano in via di disfacimento: da un termine di origine gallica (camminum) il primo, e da mitarium, aggettivo sostantivato del termine classico semita, il secondo.

La pista (da pesta e, quindi, pestare, quindi “traccia”, “orma”), é il corrispondente termine che indica, alla scala del territorio, una via segnata dal solo passaggio frequente di persone e animali. Anche se alcune piste rimangono persistenti per secoli esse rappresentano, per loro natura, una forma precaria e instabile di percorso, non consolidata da strutture insediative, le quali si pongono invece come sole polarizzazioni. Si pensi alle carovaniere, il cui scopo era la percorrenza di un territorio al fine di collegare direttamente due insediamenti urbani , a volte con strutture specialistiche di supporto quali, nel mondo islamico, i caravanserragli disposti ad intervalli di un giorno di marcia. La struttura della carovaniera obbedisce dunque ad un principio formativo diverso da quello della strada, che svolge anche un ruolo strutturante nei confronti degli insediamenti produttivi. Una chiara testimonianza di questa diversità é data, ad esempio, dalla quasi completa sostituzione da parte dei conquistatori turchi, del sistema viario anatolico romano-bizantino con carovaniere che non riutilizzavano le vecchie strade militari e commerciali, pur in condizioni ancora accettabili, con carovaniere che univano direttamente le città principali.

Un esempio di permanenza moderna di tracciati di questo genere é costituita dai tratturi (da trarre, e quindi dal latino trahere, nel senso di portare, condurre da un luogo all’altro) appenninici, sentieri naturali tracciati dalla transumanza delle greggi. In alcune regioni i tratturi costituivano fino all’inizio del secolo importanti percorsi di attraversamento a scala territoriale, collegando i pascoli, dove le greggi svernavano, ai pascoli estivi ed ai luoghi di mercato.

Al contrario dei tipi di percorsi fin qui esaminati, il termine strada contiene il concetto di stabilità, derivando da strata (sottinteso via), nel senso di via lastricata, e quindi stabilizzata in modo permanente, che richiede lo stesso procedimento critico di qualsiasi altra costruzione, così come l’etimologia di termini recenti quali carraia, rotabile, autostrada, testimonia il loro senso di percorso specializzato.

3. IL PROCESSO FORMATIVO DEI PERCORSI

Determinante é la tipologia di percorsi in rapporto alle caratteristiche idro-orografiche di un territorio, ed alle fasi che rappresentano il processo formativo del relativo sistema insediativo: si possono così distinguere i seguenti percorsi, che rappresentano, anche, una sequenza storica, da rintracciare nei documenti, per la lettura del territorio (cioé per la sua individuazione e interpretazione):

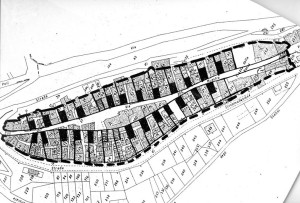

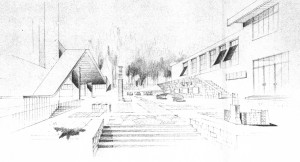

Percorso di crinale nel Volterrano. Gallicano. Nucleo urbano alla testata di un crinale secondario

Gallicano. Formazione delle corti elementari isorientate su percorso di crinale

– I percorsi di crinale, seguono l’andamento naturale della linea di spartiacque che divide due bacini idrici. Questa linea é spesso già sede di una pista territoriale naturale che collega aree diverse tra loro perché isolate dalla conformazione orografica del suolo (bacini idrici).

La ragione della formazione della più antica struttura di percorrenze di un territorio a partire dal crinale delle aree montuose è da ricercare proprio nella scala di questi collegamenti, ma anche nella possibilità di orientamento garantita dal seguire l’inviluppo dei punti geograficamente più elevati di un territorio, oltre al vantaggio di evitare i problemi di attraversamento delle basse pianure, spesso ancora paludose nelle prime fasi di strutturazione del territorio, e comunque di più problematico attraversamento per la necessità di superare, se non si rimane all’interno di un singolo bacino idrico, i guadi e i valichi che comporta. Nella primitiva formazione dei percorsi di crinale è da ricercare la ragione per la quale, come afferma anche Fernand Braudel , la civiltà si evolve dalla montagna verso il mare, contrariamente a quanto la nostra “civiltà di pianura” indurrebbe a credere. Va anche notato, fattore non secondario delle scelte nella prima fase di antropizzazione, che il percorso di crinale non richiede rilevanti opere di adeguamento del suolo essendo la sua sezione pressoché orizzontale.

A seconda dell’importanza del sistema montuoso cui sono associati i percorsi di crinale sono gerarchizzati in:

– percorsi di crinale principale, seguono le catene principali e costituiscono la sede naturale per le penetrazioni territoriali attraverso la discesa ai diversi bacini idrici. Vengono strutturati di preferenza dove é possibile utilizzare lo spartiacque più continuo.

Nell’ Italia centro-meridionale i percorsi di crinale principale, di pura percorrenza perché utilizzati per i soli spostamenti territoriali nord-sud, si sono formati già nell’età del rame e del bronzo, e sono costituito dagli spartiaque della catena degli Appennini, sede naturale delle percorrenze migratorie delle popolazioni italiche. Si distingue un crinale italico più alto, verso la costa adriatica, ed un crinale etrusco, meno continuo e rilevato, verso la costa tirrenica.

– percorsi di crinale secondario, potenziali crinali insediativi che seguono le linee spartiacque che si dipartono dal crinale principale, costituendo l’accesso ad altrettanti promontori che si affacciano su valli, direttamente o attraverso promontori secondari. Nell’ Italia centro-meridionale sono evidenti le serie di crinali secondari che, partendo dal crinale italico, si dirigono verso la costa adriatica in successione serrata, seriale, e dal crinale etrusco verso la costa tirrenica in successione più distanziata.

– percorsi di controcrinale locale, che si formano come percorsi su isoipse ad alta quota e servono quindi ad unire punti nodali dei percorsi di crinale secondario. Vengono generati dall’esigenza di scambio e presuppongono non solo una struttura elementare di insediamenti stabili, ma anche una prima forma di specializzazione produttiva che renda necessario lo scambio stesso. In pratica sostituiscono, per alcuni tratti, il percorso di crinale principale e si pongono su una giacitura alternativa ad esso. I percosi di controcrinale presuppongono il raggiungimento di una elevata capacità tecnica di modificare la forma del suolo richiedendo di superare almeno un compluvio e, a differenza dei percorsi di crinale, di adattare la sezione inclinata del suolo, con scavi e riporti, alla sezione necessariamente orizzontale del percorso.

– percorsi di controcrinale continuo, che si formano come percorsi su isoipse a bassa quota e tendono a sostituire integralmente i percorsi di crinale principale.Sono percorsi di scambio a vasto raggio tra insediamenti generati da esigenze commerciali.

– percorsi di controcrinale sintetico, che sono prodotti da due crinali con guado interposto, o posti a scorciatoia di un crinale principale. Il superamento del guado ha il significato di connessione tra due aree culturali, di estensione delle connessioni e degli scambi, inducendo alla formazione di un mercato prima e, spesso, di un nucleo urbano poi.

– percorsi di fondovalle, che si svolgono, invece, seguendo le linee di compluvio del sistema orografico, risultando così opposti e complementari ai percorsi di crinale. Vengono formati alla fine del processo di impianto della struttura territoriale e sono i meno stabili, come meno stabile é l’occupazione delle pianure, che richiede continuità nel lavoro agricolo e nelle sistemazioni idrografiche relative. Si distinguono:

– percorsi di fondovalle principale, i quali non seguono in realtà la linea di compluvio: come i percorsi di crinale non seguono esattamente la linea di displuvio, per le difficoltà naturali che essa può presentare (picchi, pareti ecc.) ma si adattano ad essa attraverso raccordi di quota, così il percorso di fondovalle può non occupare la sede immediatamente adiacente ai corsi d’acqua, ma porsi, più spesso, a ridosso di essa, adattandosi ai sistemi di piccoli rilievi del terreno o seguendo le linee di margine della pianura (percorsi pedemontani).

– percorsi di fondovalle secondario, che si dipartono spesso dalle pedemontane, per seguire i compluvi delle valli comprese tra due promontori, risultando complementari ai percorsi di crinale secondario.Questi percorsi svolgono un ruolo importante di collegamento tra bacini idrici, raggiungendo i valichi a cavallo tra di essi.

Gli insediamenti si costituiscono, in forma storicamente tipica soprattutto nell’Italia centrale , a partire dai rilievi montuosi ed a scendere verso la costa, dove si saldano in una struttura organica con gli insediamenti complementari che si formano intorno ai guadi ed agli approdi.

E’ evidente come, contemporaneamente alla discesa a valle ed alla progressiva specializzazione della produzione, nasca la necessità dello scambio e dei relativi percorsi: insediamenti e percorsi sono dunque legati da uno stesso processo formativo.

Primi a formarsi sono gli insediamenti di crinale, che si formano sui crinali secondari dalla discesa dal crinale principale impiegato per i grandi attraversamenti. Processualmente, quindi, si formano prima gli insediamenti in quota, che rappresentano la prima forma stabile di occupazione del suolo, spesso al livello delle sorgive, e successivamente gli insediamenti che tendono ad occupare l’intero promontorio fino alla testata sulla valle.

L’insediamento di testata di crinale (o di basso promontorio) costituisce dapprima una polarità territoriale, seppure a scala ridotta, costituendo la terminazione (e quindi polarizzazione) di un percorso, e successivamente, un nucleo protourbano , un nodo di scambio (attraverso la formazione di nodalità di percorsi) con la valle, nel momento in cui ha origine la fase di occupazione e strutturazione delle pianure, spesso paludose, nei quali si stabiliscono gli insediamenti di fondovalle, soprattutto alla confluenza di percorsi in corrispondenza di guadi, e quindi prima della biforcazione dei fiumi, dai quali si sviluppano nuclei protourbani (per il ruolo di mercato che la nodalità territoriale assume) e quindi, nei casi di forte polarità, nuclei urbani.

Caso particolare dell’insediamento di basso promontorio è l’insediamento acrocorico, collocato su un rilievo orografico elevato rispetto all’intero territorio circostante e quindi difeso dalle caratteristiche del suolo non solo su tre lati ma sull’intero perimetro. E’ comunque evidente che, quando l’insediamento non avvenga in uno stadio avanzato della formazione del territorio per il solo controllo delle grandi vie di transito, il comportamento dell’insediamento acrocorico risponderà al principio di essere derivato dal processo formativo del crinale secondario cui è orograficamente e storicamente legato e dal quale derivano i percorsi originari che lo hanno formato.

Nel IV sec. a. C., quando inizia la colonizzazione romana e la strutturazione o il consolidamento dei fondovalle, il territorio della penisola é strutturato ancora in nuclei protourbani. Nelle aree interne appenniniche centro-meridionali gli insediamenti a carattere tribale (pagi) consistono in nuclei arroccati su promontori. In questa fase, soprattutto nell’Etruria e nella fascia costiera dell’Italia centro-meridionale, è già strutturato un sistema di poleis, città stato che risentono, spesso in modo indiretto, l’influenza della colonizzazione greca.

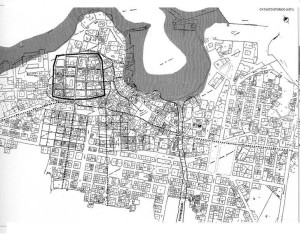

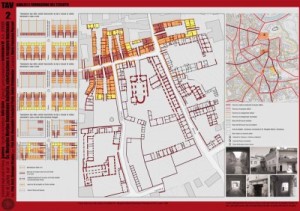

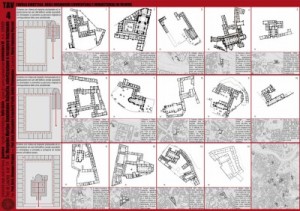

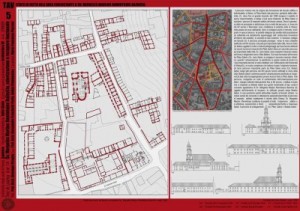

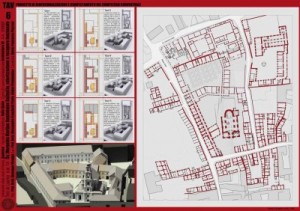

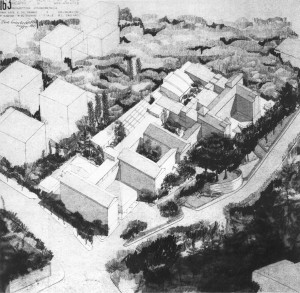

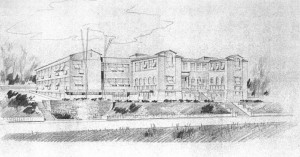

Il sistema dei percorsi in relazione all’ipotesi della formazione pianificata della città di Trani (da G.Strappa, M.Ieva, M. Dimatteo, La città come organismo. Lettura di Trani alle diverse scale, Bari 2003)

Gli insediamenti costieri di approdo sono centri specialistici per il commercio e lo scambio (in questo simili ai nodi di mercato che si formano, spesso, in corrispondenza dei guadi) dai quali si originano sulla costa nuclei urbani in corrispondenza, spesso, con insediamenti di basso promontorio più interni, alla testata di crinali secondari, con i quali viene instaurato lo scambio (non nascerebbe un approdo se non esistesse un’area produttiva da raggiungere).

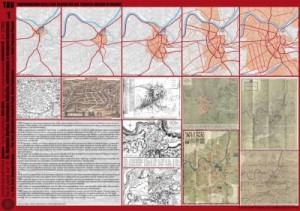

Il sistema dei percorsi e degli insediamenti si forma secondo estesi periodi temporali che corrispondono, schematicamente, ai grandi cicli della storia del territorio:

ciclo d’impianto, databile dal Paleolitico al IV sec. a.C, attraverso il quale si struttura l’intero territorio, da monte verso valle, attraverso percorsi, insediamenti, nuclei protorbani e primi nuclei urbani propriamente detti in corrispondenza dei controcrinali sintetici;

ciclo di consolidamento, databile dall’espansione romana del IV sec. a. C. al declino del IV-V sec. d. C., attraverso il quale si stabilizza la struttura già impiantata, integrata dall’organico strutturarsi dei percorsi di fondovalle e dei relativi nuclei urbani. In realtà processi analoghi e diacronici di grandi strutturazioni dei fondovalle avvengono nei maggiori bacini idrici dell’antichità, come nelle valli del Tigri-Eufrate, del Nilo, del Gange;

ciclo di recupero, individuabile nel periodo medievale tra la fine del IV-V sec. d.C. e la fine del XII sec., durante il quale si perdono le strutture di fondovalle organizzate in periodo romano e si riutilizzano e trasformano le strutture precedenti di promontorio

ciclo di ristrutturazione, corrispondente al periodo dal XIII secolo all’età contemporanea, durante il quale si riorganizzano le strutture di fondovalle parzialmente abbandonate nel ciclo di recupero, con estese opere di bonifiche.

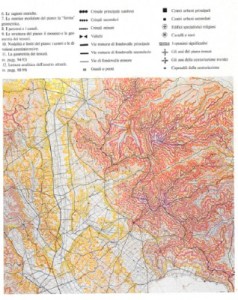

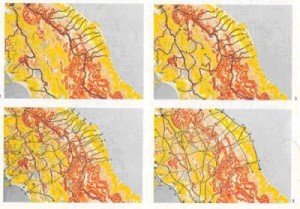

Fasi formative della struttura territoriale dell’Italia centrale (da AA.VV., Cortona, Struttura e territorio, Cortona 1987).

Formazione del sistema delle percorrenze radiali e controradiali in relazione ai fossi della Marranella, di Gottifredi, di Centocelle a Roma sulla base della carta IGM del 1872 ( da G.Strappa, a cura di, Studi sulla periferia est di Roma, Francoangeli, Milano 2012)

4. BIBLIOGRAFIA

Testi di carattere generale:

G.Strappa (a cura di), Studi sulla periferia est di Roma, Francoangeli, Milano 2012

G.Strappa, M.Ieva, M. Dimatteo, La città come organismo. Lettura di Trani alle diverse scale, Adda, Bari 2003

G.Strappa, Unità dell’organismo architettonico, Dedalo, Bari 1995 (on line su questo sito)

F. Farinelli, I segni del mondo, Firenze 1992.

F. Braudel, Civiltà e imperi del Mediterraneo nell’età di Filippo II, Torino 1986

G.Caniggia,G.L.Maffei, Composizione architettonica e tipologia edilizia. 1. Lettura dell’edilizia di base, pp. 203-249, Venezia 1979.

G. Cataldi, Per una scienza del territorio. Studi e note, Firenze, 1977

Come esempi significativi di lettura di organismi urbani particolari si possono utilmente consultare:

G.L.Maffei (a cura di), La casa rurale in Lunigiana, Venezia 1990.

AA.VV., Cortona. Struttura e storia, Cortona 1987

G.Conti, D.Corbara, Per una lettura operante della città. L’esempio di Cesena, Firenze