Territori metropolitani contemporanei

Category Archives: Archivio

Archivio

Due capitali. Nuove architetture in Kazakistan, i casi di Almaty ed Astana

Due capitali

Nuove architetture in Kazakistan

i casi di Almaty ed Astana

conferenza di

Aizhan T. Akhmedova

Kazakh Leading Academy of Architecture and Civil Engineering

KazGASA_Almaty University

introduce

Giuseppe Strappa_coordinatore Dottorato DRACO

Pisana Posocco_membro del Collegio

dei docenti del Dottorato DRACO

aula Fiorentino, via Gramsci, 53

martedi 12 novembre 2013

ore 15.00

diap sapienza

draco _ dottorato in architettura e costruzione

organizzazione: Pisana Posocco,

Valeriya Klets

progetto grafico: Valeriya Klets

ORGANICITA’ FUTURA

ORGANICITA’ FUTURA

di Giuseppe Strappa

In Città di Pietra – L’altra modernità, catalogo della X Biennali di Architettura di Venezia, Venezia 2006.

Il tema della sezione “Città di pietra” all’interno della Biennale d’architettura del 2006, ripropone alla riflessione alcuni temi fondanti delle discipline di progetto che sono stati a lungo ritenuti superati senza che alcun dibattito o, almeno, pensiero compiutamente espresso, ne avesse dimostrato la reale inattualità.

Credo che tra questi temi abbia un ruolo centrale, per il carattere fondante che possiede, quello relativo al principio di organismo e organicità, che informa appieno la nozione stessa di architettura mediterranea. Principio che sembra entrare, secondo una critica sbrigativa quanto settaria, in collisione con i portati più evidenti del pensiero contemporaneo: sembrerebbe non contenere e comprendere le radici profonde delle trasformazioni che sono alla base della formazione della città moderna e le modificazioni che determinano le condizioni di crisi della città contemporanea. Sotto questo riguardo il metodo di leggere la realtà costruita come organismo, a partire dal suo processo formativo, viene non di rado considerato, da una parte, strumento di pacificazione e conciliazione delle lacerazioni prodotte dalle trasformazioni dell’ultimo mezzo secolo ottenuto in vitro, nell’universo perimetrato e protetto dei riferimenti alla tradizione, secondo un consolidato luogo comune che vuole leggere la storia come luogo dell’armonia e la modernità come dissonanza, dall’altra una sorta di archeologia del territorio inapplicabile alla città contemporanea, per la quale l’unica nozione utilizzabile sembra essere quella di “complessità”. Nozione in realtà ormai vaga proprio per essere divenuta, nell’uso, onnicomprensiva: che sembra documentare, ma non spiegare, la contemporanea frammentazione dell’unità formativa dell’architettura della città. Nessuno sembra chiedersi se dissonanze e frammentazioni, il disordine che sembra mostrarsi privo di significato, non siano in realtà lo strato superficiale di cambiamenti profondi, l’aspetto visibile di strutture in formazione, il segno ancora oscuro, come sempre nella storia, del nuovo ordine che sta emergendo.

Non c’é dubbio che le tecniche di progettazione abbiano subito, negli ultimi due secoli, un progressivo fenomeno di astrazione: dalla conoscenza diretta del paesaggio costruito si è passati alla conoscenza indiretta derivata dall’accumulo di riproduzioni del paesaggio reale (descrizioni comunque critiche e dunque inevitabilmente deformate del reale, che pongono un’attenzione “di parte” su alcuni aspetti dell’oggetto descritto, trascurandone altri) fino agli odierni modi di percezione, esclusivamente mediati. La percezione contemporanea, filtrata e indiretta, contribuisce a separare le forme tra loro rendendole autonome, impedendo di cogliere l’intervallo prezioso tra le cose. Che diviene vuoto.

Siamo dunque di fronte ad una crisi che ha caratteri inediti rispetto alle grandi fasi critiche, di transizione, che hanno percorso fino ad oggi la storia della città e del territorio: l’interpretazione artificiale e mediatica del mondo si sovrappone alla percezione naturale della realtà, consentendo di “liberare” la forma dal suo alveo concreto, di staccarla dai legami organici che la tengono unita agli altri prodotti dell’antropizzazione del territorio: di proporre forme analoghe a quelle del mondo reale letto nella sua disgregazione ponendo problemi, e questo è uno dei nodi della questione, appartenenti tradizionalmente ad altre discipline “descrittive” che operano di diritto sulla forma staccata dalla realtà. Trascurando così che l’architettura, nella sua essenza, non è descrizione (né imitazione o interpretazione) della realtà: è la realtà. E separando, nello spazio e nel tempo, le forme dalla loro cornice naturale, tranciandone le relazioni reciproche e dunque perdendo la possibilità di leggerne la ricchezza, la complessa necessità reciproca nel grande flusso delle trasformazioni del paesaggio costruito. L’organicità dell’edificio, della città, del territorio, non risulta leggibile, infatti, nella forma “principale” sulla quale si focalizza l’interesse dell’osservatore, ma nello spazio che è generato dall’incontro, dall’intervallo o dall’ intersezione tra le forme, che dimostra la con-formazione dell’elemento, la sua maggiore o minore predisposizione ad accogliere il rapporto con altri elementi, a disporsi all’aggregazione, a formare unità di grado maggiore. Spazi che nelle periferie, nei margini conflittuali e irrisolti della città contemporanea hanno acquisito la dimensione di grandi schegge nelle quali, tuttavia, non si compie lo sforzo di riconoscere la traccia alterata della forma che precede l’esplosione. Se non si coglie il senso delle polarità delle quali è intersezione, lo spazio ibrido e vago delle periferie finisce col ricadere nel grande mare del pittoresco metropolitano e l’unica spiegazione della forma che assume la complessità finisce con l’appartenere al dominio della statistica: il reale come caso particolare e fortuito del possibile. La nuova retorica del vuoto può essere letta, per questa via, come rifiuto della concretezza dello spazio-intervallo tra le forme, prodotto dell’indagine analitica delle molte espressioni della città e del territorio che riduce ogni oggetto a frammento, ogni forma a rovina, ovvero resto di un processo di mutazioni separato dalla propria dimora organica (si vedano in proposito le anticipatrici considerazioni di Paul Virilio sulla dematerializzione del paesaggio urbano e l’irruzione di tecnologie dell’immagine virtuale in L’orizon negatif, Paris 1984).

In altri termini, il contributo della nozione di organismo alla lettura della città contemporanea ritengo possa consistere in un richiamo, critico e vitale, alla realtà: nel dimostrare come non esista il vuoto se non nel modo contemporaneo di percepire il mondo come dematerializzazione della realtà fenomenica, nell’immagine astraente che separa lo spazio dai propri contorni, i quali in realtà lo in-formano, danno aspetto riconoscibile, nella loro interezza, a sequenze di strutture e processi operanti, altrimenti invisibili.

Mi sembra che la leggittimità di questo contributo sia messo in crisi da quattro condizioni al contorno che sembrano vanificare ogni sforzo di aggiornamento della nozione di organismo.

1. A conforto delle tesi sull’obsolescenza della nozione di organismo si aggiunge oggi una nuova, evidente condizione, mai sperimentata prima d’ora in termini tanto estesi, di enorme abbondanza di risorse disponibili nel mondo occidentale. Condizione che ha inciso profondamente anche nel modo di concepire l’economia dell’architettura col rendere meno stringenti alcune fondamentali necessità nei rapporti interni tra parti dell’organismo architettonico e urbano.

Da tempo il termine “consumismo” è entrato nel novero delle parole abbandonate, retaggio innominabile di un sociologismo polveroso. La spiegazione è semplice: in realtà la logica onnivora del consumo (unitamente a quella ad essa inevitabilmente collegata della competizione) è talmente connaturata alla condizione contemporanea da essere divenuta invisibile alla critica, da costituire il vero terreno di coltura e di confronto dell’innovazione in architettura.

Con effetti, peraltro, spesso dannosi, come nel caso della costruzione dellaTrés Grande Bibliothéque di Parigi, il cui progetto, come nota J.M.Mandosio (L’effondrement de la Trés Grande Bibliothéque, Parigi 1999), si adegua con tanta partecipazione alle richieste di “spendibilità” politica dell’immagine, da lasciare irrisolti i problemi legati alla natura stessa dell’organismo architettonico.

Il limite antimoderno ma anche, allo stesso tempo, la forza stessa del metodo progettuale legato alla nozione di organismo, risiede nella sua attitudine esemplificativa e dimostrativa della realtà, nel prefigurare un mondo di regole depurato e semplice (simplex come contrario di multiplex) : un processo di riduzione critica della realtà dunque che, come tale, contiene allo stesso tempo, si noti, complesse scelte interpretative e programmatiche. La “semplificazione critica” prende atto della complessità-multiformità del costruito e si pone, in questo senso, non diversamente da ogni ipotesi scientifica, come risultato di un atto di selezione: la possibile sintesi unificante ricercata in quanto la realtà costruita contiene di tipico e generalizzabile, come uno strato geologico profondo che si modifica con lentezza al di sotto del flusso delle improvvise e caotiche trasformazioni superficiali. Forzando un po’ la mano possiamo dire che, come in qualsiasi testo, noi leggiamo nella città e nel territorio quello che vogliamo e possiamo leggere (in questo senso la lettura non è mai neutrale ma è, essa stessa, progetto). Se si osserva la realtà costruita con l’ottica cui abbiamo fatto cenno, non è difficile riconoscere come sopravviva, potente, un sostrato culturale che induce all’uso di forme e tecniche costruttive specifiche e differenziate all’interno di aree che hanno sviluppato, storicamente, caratteri comuni: ancora, e di nuovo, sono oggi riconoscibili i diversi aspetti, perfino nella sperimentazione architettonica, tipici delle aree a tradizione elastica e di quelle a tradizione plastica dando luogo ad una possibile individuazione di caratteri, se non omogenei, almeno leggibili con una certa costanza, interni alle aree di tradizione seriale e gotica (non solo nordeuropee ma anche nordamericane) e di tradizione organica e mediterranea.

Funzione ordinatrice e semplificatrice, si diceva, la quale costituisce, si badi, tutt’altro che la banalizzazione dei dati della realtà. Al contrario la semplificazione rappresenta l’atto complesso di riconoscere la struttura portante del problema che permette di superare l’accessorio, il dettaglio, il complemento secondario destinato ad uniformarsi (a comporsi in unità) secondo la traccia generale disegnata nell’insidioso groviglio di segni che ogni paesaggio contemporaneo contiene. Metodo che ha pieno diritto, ritengo, a rivendicare una possibile attualizzazione: la lettura dell’esistente non può, in realtà, oggi, avvenire nella “piena innocenza” della pura constatazione, per le molte conseguenze che il modo di leggere e progettare la città per parti (e la città letta “per frammenti” non ne è che la conseguenza estrema) ha avuto sullo sviluppo disastroso della città europea degli ultimi quarant’anni.

2. E’ evidente che la diffusione a rete degli scambi e la globalizzazione dell’informazione sono tra i fenomeni contemporanei quelli che possiedono, insieme ad una grande forza di suggestione, le maggiori potenzialità di trasformazione della vita urbana; e tuttavia, nonostante le teorie più aggiornate vi facciano continuo riferimento, non sembra essere stata elaborata alcuna proposta credibile che metta in relazione tali fenomeni con la possibilità del controllo progettuale della realtà costruita, né alcun disegno di architettura è riuscito ad includere, se non attraverso la suggestione dell’immagine analogica, l’innovazione delle mutazioni della comunicazione diffusa.

La quale ha già prodotto da tempo, peraltro, i suoi effetti traumatici nella vita quotidiana con l’introduzione delle reti telefoniche, seguita dalla diffusione del fax e della posta elettronica. In realtà l’architettura possiede una sua non eliminabile fisicità in grado di accogliere soprattutto le mutazioni che riguardano l’ambiente fisico. Molto più delle nuove forme di comunicazione immateriale, i cambiamenti indotti dalla “fisicità” delle forme di trasporto meccanizzato hanno contribuito all’aggiornamento degli edifici, dei tessuti, delle strutture del territorio. Si pensi, a fronte dell’ impatto relativamente scarso prodotto dall’uso del telegrafo o della posta pneumatica, alla rivoluzione operata dall’ introduzione dell’ascensore nella forma degli edifici. L’edificio specializzato seriale assumeva, tradizionalmente, la forma di un tessuto nel quale veniva operato un ribaltamento dei percorsi all’interno (il palazzo, ad esempio, il convento e gli infiniti tipi edilizi da essi derivati). Rispetto a questi percorsi tradizionali, soprattutto orizzontali, i vani scala non potevano che porsi, per la brevità del loro sviluppo, come prosecuzione o comunicazione tra percorsi e la cui lunghezza veniva limitata da evidenti ragioni antropiche. Con l’irruzione del trasporto meccanizzato il vano ascensore diviene un vero e proprio asse che individua un percorso verticale sul quale si impiantano, seppure instabilmente, percorsi secondari orizzontali che distribuiscono i diversi piani. Viene così ricostruita, in verticale, la logica della gerarchizzazione delle percorrenze di un tessuto, aprendo fisicamente una terza dimensione all’incremento dell’organismo aggregativo: con le dovute cautele e revisioni, la processualità formativa delle torri nella metropoli contemporanea, permette ancora di riconoscere la presenza della nozione, aggiornata, di tessuto.

Si pensi poi, passando dalla scala dell’organismo edilizio a quella dell’organismo urbano e territoriale, all’innovazione costituita dall’introduzione delle linee tranviarie e metropolitane, delle reti ferroviarie, fino all’attuale meccanizzazione totale: da un luogo della terra all’altro il viaggio avviene oggi solo attraverso la mediazione della macchina (l’auto o il treno metropolitano, il nastro trasportatore, la scala mobile, l’aereo e poi di nuovo la scala mobile, il nastro trasportatore, il treno metropolitano o l’auto) in una sequenza razionale di percorsi che acquisisce un proprio carattere (riconoscibile e programmabile) distributivo, spaziale, estetico. Accanto a questi fenomeni riconducibili entro l’alveo generale del processo di mutazione dei caratteri tipici della città e del territorio, gli altri fenomeni dovuti alla formazione delle reti di comunicazione immateriale (il decremento nella gerarchizzazione dei centri o de-centramento; l’instabilità del rapporto tra attività produttiva e luogo, o de-localizzazione) intervengono come indicazione generale che non può essere articolata in tutta la sua imprevedibile complessità. La quale deve essere ridotta alla sua essenza di orientamento, alla previsione di comportamenti “elastici” ma, riteniamo, non labili.

All’interno della tendenza largamente diffusa alla mitizzazione estetica della contemporanea congestione della metropoli e del territorio, la diade progetto – realtà si può quindi riconoscere nella coppia di termini contrapposti e complementari semplificazione – complessità, dando origine alle due nozioni di realtà semplificata e complessità progettata dove la prima indica la conoscenza della funzione critica non solo del progetto, ma anche della lettura di cui il progetto è parte costituente, mentre la seconda si associa al ruolo astraente del progetto contemporaneo, che tende a proporre come fine dell’architettura non lo scioglimento (o almeno il razionale controllo) della complessità intesa come multi-forme (come forma multipla nella quale riconoscere l’unità di grado superiore) ma, come cercherò di chiarire, la sua comprensione generale, l’espressione sintetica dell’ unità frammentata come plesso inestricabile.

3. In questo senso le teorizzazioni dei ricercatori della complessità (il cui fitto stuolo di più o meno dichiarati epigoni ha contribuito in modo rilevante alla contemporanea dispersione del ruolo dell’architettura e dell’architetto) si pongono come cosciente lettura semplificata della realtà alla quale fa seguito un artificioso progetto della complessità.

Tutte le contraddizioni economiche e sociali che hanno condotto alla formazione della metropoli contemporanea come gigantesco nodo territoriale inestricabile, terribile ed affascinante, vengono colte sinteticamente e semplicememte nel loro valore estetico di individuazione dei caratteri estremi della complessità urbana, da riproporre con gli strumenti della descrizione, e quindi fondamentalmente letterari, nella progettazione del nuovo, anche in aree culturali dai caratteri radicalmente diversi.

La Manhattan della Delirious New York raccontata da Koolhaas, non a caso, è il luogo deputato alla trasformazione permanente che contiene non solo l’immagine della mutazione, dell’irrazionalità e dell’utopia, ma anche degli strati di architetture possibili, layers di progetti abortiti che costituiscono possibili alternative alla realtà costruita. L’ interpretazione critica e processuale che la “cultura della congestione” in qualche modo contiene, mette in evidenza la crescita programmaticamente antiorganica della metropoi contemporanea, l’estremizzazione delle sue matrici seriali, lo sviluppo per addizioni continue in conflitto tra loro. Ma la critica di Koolhaas contiene, anche, la presunzione di progettare la casualità del molteplice letto nei suoi frammenti separati: l’evocazione della complessità dei suoi primi progetti per Le Havre, Lille, Karlsruhe, finisce per divenire il gesto del samana , per apparentarsi al rito taumaturgico che media forze irrazionali, misteriose, incontrollabili. Perduta la pertinenza con la propria fase storica e con la propria area culturale (tolte dal loro tumultuoso contesto economico e antropico) le forme delle torri-grattacielo si trasformano in oggetti di evocazione, non dissimili, in fondo, dalla (ormai) nostalgica imitazione di modelli e comportamenti lontani e mitizzati, diffusi in Europa almeno a partire dal secondo dopoguerra. Una tecnica di seduzione, evocatrice di un mondo nuovo della densità e dell’accelerazione, dove le contraddizioni sembrano di volta in volta, illusoriamente e paradossalmente, sciogliersi per eccesso di concentrazione.

Ma non è affatto detto che l’architettura del futuro, sulla scia, in fondo, delle visioni che da Jules Verne a Le Corbusier, da Marinetti a Robert Moses hanno percorso l’immaginario occidentale moderno, dovrà prendere le forme del mondo della velocità, della macchina, dell’intensificazione dei flussi. Ne’ che il fascino della scoperta del caos latente nell’Universo, delle nuove teorie scientifiche che ipotizzano l’indeterminatezza del rapporto tra causa ed effetto, sia qualcosa di più che una giustificazione vaga ed effimera di una frammentazione (di una perdita della capacità di leggere il generale negli infiniti particolari che la realtà di continuo propone) che ha invece ragioni interne alla crisi di trasformazione che l’architettura periodicamente subisce nei momenti di grande passaggio epocale.

E’ invece possibile che, passata l’euforia analogica e lo stupore per i cambiamenti in atto, l’architettura della città futura, sulla scia della grande tradizione mediterranea, aggiornata dal portato dei tempi, risulti fondata sull’aggregazione di grandi vani vuoti capaci, anche, di contenere il fragore dei grandi flussi di una popolazione instabile, rumorosa, migratoria senza per questo inseguire un’impossibile adeguamento ad ogni cambiamento in atto: tutto quanto è destinato a seguire una mutazione, non può che prescindere dalle forme della mutazione stessa, dovendo possedere una solidità di grado superiore, capace di ospitare l’incognito. Il naufragio dei miti della “dimensione umana”, delle tante macchine per abitare, curare, riunire disegnate dagli architetti, ha mostrato, oltre ogni ombra di dubbio, la necessità di separare il mutevole, l’accessorio, il transeunte (la parte mobile e fragile del costruito) dalla solidità della pietra che sostiene e separa. Per questo le nostre città torneranno ad essere, nell’organicità dei loro caratteri, città di pietra, anche se la pietra sarà sostituita da altri materiali a carattere murario (in questo senso l’architetto contemporaneo è il primitivo del nuovo millennio il quale, di fronte delle nuove materie che la scienza e l’industria gli propongono, tenta di riconoscerne faticosamente i caratteri, il processo attraverso il quale la materia nuovissima può essere trasformata in materiale.

Questa architettura (della quale sembrano già emergere i segni di un’inaugurale poesia) darà i suoi prodotti esemplari, non diversamente dalle basiliche e dai fori dell’antichità mediterranea, proprio nelle grandi infrastrutture a contatto con la velocità e con la macchina: nelle fabbriche dove una tecnologia in continua evoluzione non permette alla forma di adeguarsi a funzioni provvisorie, in continuo mutamento, ma soprattutto nei grandi nodi di scambio territoriale. In tutti quei luoghi, in altre parole, dove la complessità deriva dalla mancanza (dall’impossibilità) di riconoscimento dei nessi tra le cose: riconoscere l’aeroporto (ma anche la stazione della metropolitana, lo scalo dei container ecc.) come nodo di una struttura di percorrenze risulta infatti impossibile di fronte alla mancanza di visibilità fisica della rete di trasporto. E tuttavia sarebbe semplicistico leggere l’aeroporto come frammento, le stazioni delle subways come tessere disperse nel flusso delle trasformazioni urbane. L’architettura dovrà farsi carico, al contrario, anche del non visibile, dell’organicità non direttamente leggibile che lega gli aeroporti tra loro, come pure le stazioni delle metropolitane e i nodi dell’alta velocità. Non è un caso che le nozioni di organismo e tipicità riemergano proprio nei contesti dai quali, come espressione riconosciuta della modernità, dovrebbero essere più lontane.

4. Ultimo e consolidato aspetto della questione che prenderemo in esame: la pretesa obsolescenza della nozione di tipicità, strettamente connessa a quella di organismo, a fronte del vortice del cambiamento nei processi produttivi insorto con la modernità ed esasperato dalla crisi contemporanea.

Forse occorrerebbe riflettere, più di quanto non sia stato fatto fino ad ora, sulla permanenza della nozione di tipo nell’architettura moderna: gran parte della didattica e della produzione storiografica contemporanee continuano a proporre l’architettura moderna come risultato di una grande koinè innovatrice la cui coesione era basata su una sorta di eroica negazione del tipo.

Questa negazione, ultima difesa di un tenace individualismo tardoromantico, effettivamente latente in molti manifesti della modernità, era in larga parte dovuta alla condizione di crisi indotta dall’irruzione della macchina, considerata come innovazione improvvisa che causa il mutamento fulmineo, la rivoluzione estesa ad ogni campo delle attività umane, e quindi, anche al carattere degli edifici.

Orbene, considerando la macchina, anche nella sua versione aggiornata di hardware, sotto un diverso, più realistico punto di vista, non si può non riconoscere il suo evidente contenuto tipologico.

Consideriamo, ad esempio, il divario tra ruolo dell’aeroplano nell’immaginario moderno e la sua essenza fenomenica di prodotto industriale. Dal paragone fra il processo di mutazione dei tipi di edificio e dei tipi di aeroplano nascono sorprendenti analogie: non esiste aereo che sia stato totalmente inventato, ma famiglie di aeroplani dove ogni nuova macchina costituisce un aggiornamento della macchina precedente: si pensi alle grandi famiglie di macchine abitate, ai Latécoère, ai Caproni ammirati da Le Corbusier, ognuna deposito di esperienze e innovazioni, piccole e grandi modificazioni, specializzazioni successive. E, poi, alla trasformazione dei materiali: accanto agli esperimenti, nella produzione corrente, negli edifici come nelle macchine, i cambiamenti improvvisi nei materiali non portano immediatamente a forme nuove: aerei costruiti dapprima in legno e successivamente in metallo rimangono pressoché identici per un tempo relativamente lungo, mantenendo i caratteri del tipo, poi aggiornato sviluppandone nuove potenzialità. Ogni tipo è così pertinente alla propria fase storica: il tipo sperimentale, assolutamente innovativo, non può trovare applicazione che nell’ambito ristretto del laboratorio. Negli anni ’30 è stato costruito, negli Stati Uniti, dalla Douglas, un aereo straordinario, realizzato a seguito di un’inchiesta sulla domanda di innovazione nei trasporti, che conteneva tecnologie degne di una macchina degli anni’70. Eppure, nonostante il costo di sviluppo avesse raggiunto i 30 milioni di dollari, questa macchina non è stata immessa sul mercato poiché le condizioni tecnologiche ed economiche, la cultura tecnica, l’intero contesto nel quale avrebbe dovuto operare, non consentivano di recepire la rivoluzione proposta.

Se si prescinde dalle semplificazioni di una storiografia di parte, i documenti della vicenda italiana dell’ architettura moderna mostrano, peraltro, come fosse evidentissima la coscienza del limite culturale e storico dell’innovazione anche nel processo di identificazione tra edificio e macchina.

Basterà rileggere, in proposito, alcuni passaggi del manifesto pubblicato nel 1926 dal Gruppo 7, una delle prime teorizzazioni italiane dell’architettura moderna: “Le nuove forme dell’architettura dovranno ricevere il valore estetico dal solo carattere di necessità,e solo in seguito per via di selezione nascerà lo stile. Si è detto per selezione,questa parola sorprende. Aggiungiamo: occorre persuadersi della necessità di produrre dei tipi,pochi tipi fondamentali. Questa necessaria, inevitabile legge incontra la più grande ostilità,la più assoluta incomprensione. Ma guardiamoci indietro,tutta l’architettura di Roma nel mondo è basata su 4 o 5 tipi e tutta la sua forza sta nell’aver mantenuto questi schemi,ripetendoli e perfezionandoli per selezione,appunto. Ma l’idea della casa tipo sconcerta, spaventa,suscita i commenti più grotteschi e più assurdi. Si crede che fare delle case tipo, in serie, significhi meccanicizzarle, costruire edifici che somiglino ai piroscafi e agli aeroplani. Deplorevole equivoco,nell’architettura non si é mai pensato di ispirarsi alla macchina. L’architettura deve aderire alle nuove necessità come le macchine moderne nascono da nuove necessità e si perfezionano con l’aumentare di quelle. La casa avrà una sua nuova estetica, come l’aeroplano ha una sua estetica,ma la casa non avrà quella dello aeroplano”.

Passaggio che, mi sembra, possa costituire in questo contesto non solo lo scioglimento di un equivoco ancora persistente nel dibattito in atto, ma anche la prefigurazione, assolutamente limpida, di un’alternativa, di una via organica e processuale alla deriva estetizzante e tardoromantica dell’architettura contemporanea.

LETTURA DEL TERRITORIO

PROF. GIUSEPPE STRAPPA

1. IL TERRITORIO COME ORGANISMO

Il territorio è architettura nel suo significato più pieno.

Esso nasce dalla collaborazione tra uomo e natura.

La derivazione etimologica del termine (da terra contrapposto al termine mare) contiene la nozione di luogo abitato, quindi trasformato, costruito e ricostruito dalla mano dell’uomo, contrapposto a quella di luogo inabitato.

Il territorio è anche una grande eredità civile, un patrimonio nel quale sono inscritte le scelte e le trasformazioni operate dalle popolazioni che vi sono vissute. Per questo ogni intervento a questa scala obbliga alla comprensione dei caratteri che possiamo conoscere attraverso la sua forma, sapendo che questa forma è l’esito riconoscibile di un processo in atto.

Essendo il territorio costituito da parti collaboranti, è possibile leggerlo attraverso la nozione di organismo, cioè di insieme di elementi, strutture, sistemi legati da un rapporto (variabile nel tempo) di necessità. E come in ogni organismo è possibile riconoscere nel territorio fasi e cicli storici che ne determinano la formazione, la trasformazione, la frammentazione, la rovina.

Quella di organismo territoriale come luogo abitato costituito di parti collaboranti (percorsi, insediamenti, aree produttive) è, dunque, una nozione complessa che sintetizza i processi analizzati a tutte le scale minori: organismo edilizio, organismo aggregativo, organismo urbano.

Il concetto di territorio deriva dal nesso che lega l’idea di suolo naturale a quella delle trasformazioni artificiali operate dall’uomo nel processo di antropizzazione (trasformazione abitativa e produttiva) del suolo stesso. Noi cogliamo questo processo attraverso momentanei stati di equilibrio che restituiscono un’idea discreta di una sequenza storica che è, invece, flusso continuo di modificazioni e rivolgimenti.

Per questo non è comprensibile il senso storico-processuale di un organismo urbano o di un sistema di percorrenze, se non si colloca la loro formazione all’interno di un rapporto di necessità con l’insieme delle relazioni instaurate nel tempo e nello spazio entro il proprio intorno territoriale. Questa forma del territorio antropizzato non é che l’aspetto visibile di una struttura di relazioni che lega nella nozione di organismo i diversi gradi scalari del costruito e che indicheremo col termine “paesaggio”.

L’organismo territoriale si forma e sviluppa secondo processi differenziati storicamente ed arealmente che possiedono, tuttavia, una loro tipicità, al pari di ogni altro esito del processo antropico. Si può parlare dunque di “tipo territoriale” come insieme dei caratteri fisici processualmente ereditati (patrimonio) comuni ad un intorno storico-geografico, ovvero come insieme delle nozioni e scelte insediative comuni che determinano il complesso delle operazioni di trasformazione del luogo naturale in luogo abitato.

Questa tipicità di comportamento si individua (assume caratteri individuali, unici, irripetibili) nelle trasformazioni reali del suolo determinate nello spazio e nel tempo in funzione di variabili naturali (sistema oro-idrografico, natura geologica del suolo ecc.) e storiche (in relazione, cioè, ad una determinata fase civile). Grazie alla nozione di tipicità è possibile riconoscere il maggiore o minore grado di organicità di un territorio, il quale può essere costituito anche da elementi relativamente autonomi e seriali, che comunque risultano polarizzati da un ordine formativo (dislocativi) più generale, insito nella nozione stessa di organismo.

A somiglianza di quanto avviene nel primo e più elementare dei processi di trasformazione antropica, cioé della materia in materiale, anche l’ultimo e più complesso fenomeno di trasformazione del suolo naturale in suolo abitato é relazionato a scelte operate attraverso un processo di selezione e specializzazione.

– la selezione (da seligere, scegliere) deriva dalla coscienza della differenza tra le cose e dal riconoscimento della loro idoneità ad essere utilizzate e trasformate. L’operazione di selezione è qui intesa come scelta dell’attitudine di un suolo ad essere percorso, ad essere trasformato per uso abitativo o produttivo; potrebbe essere identificata come momento logico nel rapporto di collaborazione tra uomo e natura, quello attraverso il quale vengono valutate le diverse possibilità degli elementi componenti ad essere utilizzati, eventualmente dopo convenienti trasformazioni;

– la specializzazione, è l’attività di restringere e trasformare i caratteri di una cosa per renderla adatta a particolari finalità. Deriva dall’individuazione del rapporto di complementarità e necessità tra le cose. L’operazione di specializzazione è qui intesa come trasformazione di parti di suolo in funzione dei particolari ruoli che devono svolgere all’interno dell’organismo territoriale. Gerarchizzandosi, ad esempio, i percorsi assumono caratteri e qualità diverse in relazione al rapporto che instaurano con l’insieme del territorio. In questo senso la stessa costruzione che, se vista sotto il solo aspetto tettonico può essere considerata trasformazione finalizzata di materia, può qui essere intesa secondo la diversa ottica di modificazione specializzata di una porzione di territorio. La specializzazione può essere identificata come momento tecnico-economico nel processo di antropizzazione del territorio, quello nel quale interviene la finalizzazione individuale, cui succederà una finalizzazione collettiva e una sintesi organica leggibile.

Queste operazioni possono essere lette attraverso una prima, fondamentale diade di termini opposti e complementari composta da “insediamenti” e “percorsi”, legati al moto ed alla sosta in funzione dei bisogni primordiali dell’uomo di proteggersi e alimentarsi.

Da quanto esposto si riconosce al termine “insediamento” il significato di struttura provvisoria o stabile costituita da un insieme di abitazioni relazionate organicamente ad un’area complementare produttiva. Potremmo pensare i primi insediamenti provvisori, come appartenenti alle civiltà dei cacciatori e raccoglitori, seguiti da insediamenti semistanziali, legati alle prime forme di coltivazione o allevamento, dove la nozione di dimora (etimologicamente derivata da de-morari, indugiare, con il senso di permanenza in un luogo) viene associata più stabilmente a quella di area di pertinenza. Il possesso di un’area é dovuto, in origine, all’appropriazione causata dal lavoro che vi veniva svolto con maggiore o minore continuità. E’ da ritenere, a questo riguardo, che le prime, embrionali forme stabili di aree di pertinenza possano essere associate alle trasformazioni antropiche dell’età neolitica, con la diffusione delle coltivazioni, soprattutto cerealicole, dovuta all’esigenza di superare l’instabilità della semplice raccolta sporadica.

Ma la definitiva nozione di associazione di un suolo alle strutture costruite dall’uomo per utilizzarlo, e cioé alle modificazioni antropiche stabili, é da ricercare in quelle fasi storiche e in quelle aree dove la necessità di continua manutenzione del suolo comportava una maggiore consuetudine tra lavoro dell’uomo e area produttiva, come nei territori dove le condizioni per la coltivazioni dovettero essere prodotte artificialmente attraverso sistemi di irrigazione permanenti che comportavano tanto una collaborazione organica tra opere artificiali e suolo naturale quanto una collaborazione organizzativa e specializzazione tra gruppi di lavoro all’interno della comunità agricola.

Questo atto di addomesticamento delle condizioni naturali del suolo, comportando trasformazioni da operare sulla natura semplicemente “incontrata”, implica infatti non solo una scelta insediativa, ma anche la chiara coscienza dell’appartenenza di un suolo alla comunità che lo lavora.

E’ un passaggio culturale che avviene gradualmente attraverso fasi successive di semistanzialità.

Nella conquista della coscienza di identità sociale (il riconoscimento dell’appartenenza al gruppo) collegata alla coscienza di identità territoriale (il riconoscimento di un suolo di pertinenza, più o meno esteso, appartenente al gruppo) consiste l’origine profonda della natura conflittuale delle trasformazioni territoriali. Natura conflittuale che, evidentemente, non é solo,come potremmo oggi dedurre dalla pura osservazione dei fenomeni di frammentazione in corso, un portato della modernità (della formazione delle grandi periferie urbane, dell’aggressione della speculazione edilizia alla condizione di equilibrio che le nostre generazioni avrebbero ereditato) ma conseguenza dello stesso processo formativo della nozione di “pertinenza” .

L’appropriazione dell’area avviene progressivamente col consolidarsi della stabilità della dimora e del rapporto di uso produttivo col suolo: dall’ allevamento brado al pascolo, dall’area di caccia alla riserva, dall’area di raccolta al suolo pubblico (in età storica l’ager publicus romano o il legnatico medievale). A partire da questi processi si svilupperà una partizione delle proprietà pubbliche e private progressivamente associate al costruito quanto più l’area mostrerà sucettibilità insediativa, dando origine al concetto giuridico di proprietà del suolo fondamentale nella dialettica formativa dell’assetto del territorio.

Processi che lasciano, ovviamente, un loro segno visibile sul territorio il qulae, per questa ragione, può essere considerato nel suo aspetto fondamentale di “documento”.

Con il passaggio dall’allevamento brado al pascolo si consolida, infatti, la nozione di recinto associata a quella di area di pertinenza nella doppia funzione di protezione e contenimento: le palizzate del neolitico avevano tanto lo scopo di proteggere quanto di impedire la fuga.

La coltivazione, inizialmente costituita soprattutto da cereali, rappresenta una rivoluzione antropica anche per la necessità di specializzazione dell’abitazione che comporta, dovendosi assicurare, associato allo spazio per la vita domestica, le strutture per la conservazione del raccolto, spesso, nelle aree eurasiatica e nordafricana, nella forma specializzata di silos circolari . Ma il processo di progressiva organicità del territorio matura solo con l’integrazione tra le diverse concause che originano la strutturazione antropica: integrazione non progrediente in modo continuo, anzi, ciclicamente conquistata e riperduta. Delle relazioni tra queste componenti che tendono a stabilire un rapporto organico tra loro, alcune hanno valore fondamentale e la relativa cartografia acquista particolare valore per il progettista:

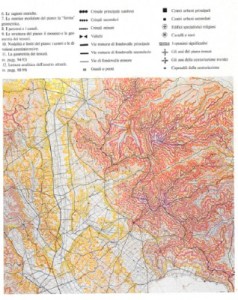

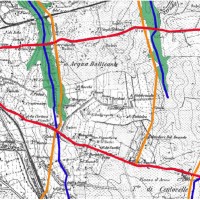

– quelle connesse alla produzione, e cioé tra insediamenti, attività agricola ed allevamento. Solo quando l’integrazione tra fertilizzazione del suolo e produzione di foraggio per l’allevamento si sviluppa in modo continuo, si può parlare di organismo produttivo associato al territorio. Associazione che diviene complessa, ma ancora processualmente leggibile, con la rivoluzione industriale. La contemporanea cartografia dell’ uso del suolo semplifica e riduce i poli e le aree di attività produttiva. Si veda come esempio la cartografia dell’Istituto Geografico Militare al 50.000 (alla fine del XIX secolo scorso) e al 25.000 (nel XX secolo).

– quelle connesse alla proprietà, e cioé tra suoli pubblici e privati. Solo quando viene stabilito e regolamentato l’uso dei suoli a disposizione della comunità integrati ai fondi privati, si può parlare di organismo fondiario (v. più oltre l’esempio del sistema a centuriatio). La cartografia catastale contemporanea semplifica la rappresentazione del territorio indicando i soli confini di proprietà alle scale 2.000 o 1.000.

Riguardato come organismo il territorio risulta composto, per la definizione generale data, da insiemi di strutture riconoscibili come concorrenti al medesimo fine, ma non autonome: segnatamente, per comprendere il processo formativo dell’organismo territoriale, occorre prendere in esame il sistema viario o sistema delle percorrenze, e quello strettamente correlato degli insediamenti , o sistema insediativo e, in seguito, una volta esaminato l’impianto generale, anche il sistema della partizione delle proprietà del suolo, o sistema fondiario, e il sistema, strettamente correlato, della utilizzazione delle risorse naturali (aree agricole e manifatturiere) o sistema produttivo, che si formano in una fase storicamente più matura del processo di antropizzazione del territorio.

Questi sistemi non svolgono compiti astrattamente di collegamento, di abitazione e produzione, ma sono inscindibilmente collegati, oltre che tra loro, al relativo sistema oro-idrografico da relazioni organiche: un promontorio naturale, separato da due displuvi, costituisce un primo intorno nel quale l’uomo riconosce caratteri specifici, trova un’identità tra gruppo e suolo naturale, così come, in una fase successiva, un bacino idrografico, isolato da confini orografici difficilmente superabili, costituisce la sede di sviluppo di un’area culturale relativamente omogenea per la facilità degli scambi interni che consente. Questi quattro sistemi, benché strettamente integrati, sono inoltre polarizzati per diadi: non solo storicamente, ma anche logicamente percorrenze e insediamenti costituiscono a loro volta sottosistemi di un sistema di maggiore complessità all’interno dell’organismo, così come fondi e strutture produttive possono essere riguardati come formanti un unico sistema unitario.

2. LETTURA E RAPPRESENTAZIONE DEL SISTEMA DELLE PERCORRENZE, DEGLI INSEDIAMENTI, DELLE AREE PRODUTTIVE

La cartografia è una rappresentazione simbolica di una porzione di territorio: come tale essa costituisce il risultato di una riduzione critica delle nozioni dedotte dall’osservazione del territorio stesso, comunicate attraverso forme simboliche.

Il simbolo (dall’indoeuropeo symballein, unire, mettere insieme), a sua volta, esprime in modo sintetico diverse nozioni considerate fondamentali: esso è dunque frutto di una scelta e di una selezione. Per questa ragione lo strumento cartografico (i simboli e la struttura che lega i simboli tra loro) è in diretta relazione con l’idea che l’autore ha espresso, all’interno di un’area culturale e di una determinata fase storica, del territorio che ha rappresentato.

Come è possibile tracciare le linee di un processo di trasformazione del territorio, così è possibile tracciare le linee di un processo di trasformazione degli strumenti cartografici. Il quale testimonia non solo (e non tanto) le mutazioni dei caratteri del territorio stesso, ma, soprattutto, la conoscenza e coscienza che, nelle diverse fasi storiche e nei diversi intorni civili, l’uomo ha avuto dell’ambiente costruito contemporaneo o del passato.

La Tabula Peutingeriana riporta soprattutto una struttura di percorsi; nell’atlante dell’Italia di Giovanni Magini (1620) non compaiono quasi i percorsi di terra; in una moderna carta automobilistica la rete stradale prende il sopravvento sulla rappresentazione degli altri dati osservabili sul territorio; la pianta di una metropolitana, infine, è soprattutto il disegno simbolico ed astratto di una rete, senza rapporto diretto con le dimensioni fisiche delle distanze tra i poli collegati.

Per il progettista, al quale occorre leggere il territorio in modo attivo, avendo come fine l’intervento, è dunque fondamentale estrarre con coerenza le informazioni dalle cartografie disponibili.

Questa coerenza costituisce il legame tra soggetto e oggetto della lettura territoriale: tra quello che il progettista cerca attraverso la rappresentazione cartografica (legata alla propria nozione di territorio ed allo scopo della lettura) e quanto le diverse cartografie possono offrire (legato alla nozione di territorio dell’autore e allo scopo della rappresentazione).

Nel seguito si riporta un criterio di lettura, legato alla nozione di territorio inteso come organismo, attraverso l’esposizione sintetica della nozione di organismo territoriale, della rappresentazione delle sue strutture (fondamentali all’interno della nozione di organismo esposta), degli strumenti operativi che permettono di estrarre dai diversi tipi di cartografia le nozioni ritenute utili.

La rappresentazione della struttura del territorio, individuata attraverso le fasi del suo uso antropico, non può che iniziare dalla lettura dei percorsi: dal modo nel quale essi si formano, si consolidano, si articolano, specializzano e gerarchizzano tra loro in modo collaborante, in rapporto di reciproca necessità secondo relazioni di congruenza e proporzione con gli insediamenti cui fanno capo. Il moto dell’uomo sul suolo, i segni lasciati dagli spostamenti, attraversamenti, migrazioni, precedono, infatti, qualunque altra traccia: qualsiasi struttura legata ad attività lavorativa e stanziamento viene associata ai percorsi, più o meno stabili, che ne permettono l’esistenza.

I percorsi, come ogni dato della realtà costruita, hanno una loro tipicità, sono cioé riconoscibili, nel loro formarsi ed evolversi, caratteri comuni che ne individuano storicamente la fase di appartenenza e, arealmente, la pertinenza ai caratteri naturali del suolo cui sono associati.

Una prima, orientativa distinzione tra percorsi tipici può essere attuata attraverso la gerarchia del compito che svolgono, e quindi attraverso le polarizzazioni che distinguono i tracciati definendone le scale:

percorsi territoriali generati in origine dalle migrazioni ed, in seguito, dai collegamenti tra aree culturali di grande polarizzazione (ne sono esempio contemporaneo i percorsi autostradali) ;

percorsi locali, interni a ciascuna area o tra aree di confine, polarizzati dagli insediamenti e dai nuclei urbani;

percorsi fondiari, collegamenti alla scala delle aree produttive;

percorsi urbani, collegamenti interni alle aree urbane.

Questi percorsi si strutturano, a loro volta, secondo gerarchie che stabiliscono rapporti organici nell’uso del territorio (abbiamo già visto, ad esempio, come nei percorsi urbani é riconoscibile un ruolo processualmente diverso dei percorsi matrice, di impianto edilizio, di collegamento, di ristrutturazione ).

Una seconda distinzione può riguardare la stabilità dei percorsi, la quale é comunque legata alla loro gerarchia e alle fasi formative.

Le più elementari e spontanee vie di comunicazione sono costituite dai cammini originati dal semplice atto del percorrere, e dai sentieri, tracciati in modo sommario dal passaggio frequente di persone e animali, come le mulattiere. E’ interessante notare come i due termini moderni non derivino da etimi impiegati nell’uso del territorio consolidato presso i romani, ma da neologismi del latino tardo, quando le strutture di percorsi consolidate erano in via di disfacimento: da un termine di origine gallica (camminum) il primo, e da mitarium, aggettivo sostantivato del termine classico semita, il secondo.

La pista (da pesta e, quindi, pestare, quindi “traccia”, “orma”), é il corrispondente termine che indica, alla scala del territorio, una via segnata dal solo passaggio frequente di persone e animali. Anche se alcune piste rimangono persistenti per secoli esse rappresentano, per loro natura, una forma precaria e instabile di percorso, non consolidata da strutture insediative, le quali si pongono invece come sole polarizzazioni. Si pensi alle carovaniere, il cui scopo era la percorrenza di un territorio al fine di collegare direttamente due insediamenti urbani , a volte con strutture specialistiche di supporto quali, nel mondo islamico, i caravanserragli disposti ad intervalli di un giorno di marcia. La struttura della carovaniera obbedisce dunque ad un principio formativo diverso da quello della strada, che svolge anche un ruolo strutturante nei confronti degli insediamenti produttivi. Una chiara testimonianza di questa diversità é data, ad esempio, dalla quasi completa sostituzione da parte dei conquistatori turchi, del sistema viario anatolico romano-bizantino con carovaniere che non riutilizzavano le vecchie strade militari e commerciali, pur in condizioni ancora accettabili, con carovaniere che univano direttamente le città principali.

Un esempio di permanenza moderna di tracciati di questo genere é costituita dai tratturi (da trarre, e quindi dal latino trahere, nel senso di portare, condurre da un luogo all’altro) appenninici, sentieri naturali tracciati dalla transumanza delle greggi. In alcune regioni i tratturi costituivano fino all’inizio del secolo importanti percorsi di attraversamento a scala territoriale, collegando i pascoli, dove le greggi svernavano, ai pascoli estivi ed ai luoghi di mercato.

Al contrario dei tipi di percorsi fin qui esaminati, il termine strada contiene il concetto di stabilità, derivando da strata (sottinteso via), nel senso di via lastricata, e quindi stabilizzata in modo permanente, che richiede lo stesso procedimento critico di qualsiasi altra costruzione, così come l’etimologia di termini recenti quali carraia, rotabile, autostrada, testimonia il loro senso di percorso specializzato.

3. IL PROCESSO FORMATIVO DEI PERCORSI

Determinante é la tipologia di percorsi in rapporto alle caratteristiche idro-orografiche di un territorio, ed alle fasi che rappresentano il processo formativo del relativo sistema insediativo: si possono così distinguere i seguenti percorsi, che rappresentano, anche, una sequenza storica, da rintracciare nei documenti, per la lettura del territorio (cioé per la sua individuazione e interpretazione):

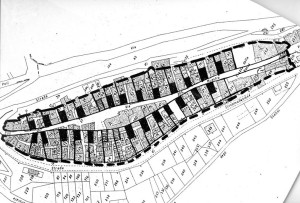

Percorso di crinale nel Volterrano. Gallicano. Nucleo urbano alla testata di un crinale secondario

Gallicano. Formazione delle corti elementari isorientate su percorso di crinale

– I percorsi di crinale, seguono l’andamento naturale della linea di spartiacque che divide due bacini idrici. Questa linea é spesso già sede di una pista territoriale naturale che collega aree diverse tra loro perché isolate dalla conformazione orografica del suolo (bacini idrici).

La ragione della formazione della più antica struttura di percorrenze di un territorio a partire dal crinale delle aree montuose è da ricercare proprio nella scala di questi collegamenti, ma anche nella possibilità di orientamento garantita dal seguire l’inviluppo dei punti geograficamente più elevati di un territorio, oltre al vantaggio di evitare i problemi di attraversamento delle basse pianure, spesso ancora paludose nelle prime fasi di strutturazione del territorio, e comunque di più problematico attraversamento per la necessità di superare, se non si rimane all’interno di un singolo bacino idrico, i guadi e i valichi che comporta. Nella primitiva formazione dei percorsi di crinale è da ricercare la ragione per la quale, come afferma anche Fernand Braudel , la civiltà si evolve dalla montagna verso il mare, contrariamente a quanto la nostra “civiltà di pianura” indurrebbe a credere. Va anche notato, fattore non secondario delle scelte nella prima fase di antropizzazione, che il percorso di crinale non richiede rilevanti opere di adeguamento del suolo essendo la sua sezione pressoché orizzontale.

A seconda dell’importanza del sistema montuoso cui sono associati i percorsi di crinale sono gerarchizzati in:

– percorsi di crinale principale, seguono le catene principali e costituiscono la sede naturale per le penetrazioni territoriali attraverso la discesa ai diversi bacini idrici. Vengono strutturati di preferenza dove é possibile utilizzare lo spartiacque più continuo.

Nell’ Italia centro-meridionale i percorsi di crinale principale, di pura percorrenza perché utilizzati per i soli spostamenti territoriali nord-sud, si sono formati già nell’età del rame e del bronzo, e sono costituito dagli spartiaque della catena degli Appennini, sede naturale delle percorrenze migratorie delle popolazioni italiche. Si distingue un crinale italico più alto, verso la costa adriatica, ed un crinale etrusco, meno continuo e rilevato, verso la costa tirrenica.

– percorsi di crinale secondario, potenziali crinali insediativi che seguono le linee spartiacque che si dipartono dal crinale principale, costituendo l’accesso ad altrettanti promontori che si affacciano su valli, direttamente o attraverso promontori secondari. Nell’ Italia centro-meridionale sono evidenti le serie di crinali secondari che, partendo dal crinale italico, si dirigono verso la costa adriatica in successione serrata, seriale, e dal crinale etrusco verso la costa tirrenica in successione più distanziata.

– percorsi di controcrinale locale, che si formano come percorsi su isoipse ad alta quota e servono quindi ad unire punti nodali dei percorsi di crinale secondario. Vengono generati dall’esigenza di scambio e presuppongono non solo una struttura elementare di insediamenti stabili, ma anche una prima forma di specializzazione produttiva che renda necessario lo scambio stesso. In pratica sostituiscono, per alcuni tratti, il percorso di crinale principale e si pongono su una giacitura alternativa ad esso. I percosi di controcrinale presuppongono il raggiungimento di una elevata capacità tecnica di modificare la forma del suolo richiedendo di superare almeno un compluvio e, a differenza dei percorsi di crinale, di adattare la sezione inclinata del suolo, con scavi e riporti, alla sezione necessariamente orizzontale del percorso.

– percorsi di controcrinale continuo, che si formano come percorsi su isoipse a bassa quota e tendono a sostituire integralmente i percorsi di crinale principale.Sono percorsi di scambio a vasto raggio tra insediamenti generati da esigenze commerciali.

– percorsi di controcrinale sintetico, che sono prodotti da due crinali con guado interposto, o posti a scorciatoia di un crinale principale. Il superamento del guado ha il significato di connessione tra due aree culturali, di estensione delle connessioni e degli scambi, inducendo alla formazione di un mercato prima e, spesso, di un nucleo urbano poi.

– percorsi di fondovalle, che si svolgono, invece, seguendo le linee di compluvio del sistema orografico, risultando così opposti e complementari ai percorsi di crinale. Vengono formati alla fine del processo di impianto della struttura territoriale e sono i meno stabili, come meno stabile é l’occupazione delle pianure, che richiede continuità nel lavoro agricolo e nelle sistemazioni idrografiche relative. Si distinguono:

– percorsi di fondovalle principale, i quali non seguono in realtà la linea di compluvio: come i percorsi di crinale non seguono esattamente la linea di displuvio, per le difficoltà naturali che essa può presentare (picchi, pareti ecc.) ma si adattano ad essa attraverso raccordi di quota, così il percorso di fondovalle può non occupare la sede immediatamente adiacente ai corsi d’acqua, ma porsi, più spesso, a ridosso di essa, adattandosi ai sistemi di piccoli rilievi del terreno o seguendo le linee di margine della pianura (percorsi pedemontani).

– percorsi di fondovalle secondario, che si dipartono spesso dalle pedemontane, per seguire i compluvi delle valli comprese tra due promontori, risultando complementari ai percorsi di crinale secondario.Questi percorsi svolgono un ruolo importante di collegamento tra bacini idrici, raggiungendo i valichi a cavallo tra di essi.

Gli insediamenti si costituiscono, in forma storicamente tipica soprattutto nell’Italia centrale , a partire dai rilievi montuosi ed a scendere verso la costa, dove si saldano in una struttura organica con gli insediamenti complementari che si formano intorno ai guadi ed agli approdi.

E’ evidente come, contemporaneamente alla discesa a valle ed alla progressiva specializzazione della produzione, nasca la necessità dello scambio e dei relativi percorsi: insediamenti e percorsi sono dunque legati da uno stesso processo formativo.

Primi a formarsi sono gli insediamenti di crinale, che si formano sui crinali secondari dalla discesa dal crinale principale impiegato per i grandi attraversamenti. Processualmente, quindi, si formano prima gli insediamenti in quota, che rappresentano la prima forma stabile di occupazione del suolo, spesso al livello delle sorgive, e successivamente gli insediamenti che tendono ad occupare l’intero promontorio fino alla testata sulla valle.

L’insediamento di testata di crinale (o di basso promontorio) costituisce dapprima una polarità territoriale, seppure a scala ridotta, costituendo la terminazione (e quindi polarizzazione) di un percorso, e successivamente, un nucleo protourbano , un nodo di scambio (attraverso la formazione di nodalità di percorsi) con la valle, nel momento in cui ha origine la fase di occupazione e strutturazione delle pianure, spesso paludose, nei quali si stabiliscono gli insediamenti di fondovalle, soprattutto alla confluenza di percorsi in corrispondenza di guadi, e quindi prima della biforcazione dei fiumi, dai quali si sviluppano nuclei protourbani (per il ruolo di mercato che la nodalità territoriale assume) e quindi, nei casi di forte polarità, nuclei urbani.

Caso particolare dell’insediamento di basso promontorio è l’insediamento acrocorico, collocato su un rilievo orografico elevato rispetto all’intero territorio circostante e quindi difeso dalle caratteristiche del suolo non solo su tre lati ma sull’intero perimetro. E’ comunque evidente che, quando l’insediamento non avvenga in uno stadio avanzato della formazione del territorio per il solo controllo delle grandi vie di transito, il comportamento dell’insediamento acrocorico risponderà al principio di essere derivato dal processo formativo del crinale secondario cui è orograficamente e storicamente legato e dal quale derivano i percorsi originari che lo hanno formato.

Nel IV sec. a. C., quando inizia la colonizzazione romana e la strutturazione o il consolidamento dei fondovalle, il territorio della penisola é strutturato ancora in nuclei protourbani. Nelle aree interne appenniniche centro-meridionali gli insediamenti a carattere tribale (pagi) consistono in nuclei arroccati su promontori. In questa fase, soprattutto nell’Etruria e nella fascia costiera dell’Italia centro-meridionale, è già strutturato un sistema di poleis, città stato che risentono, spesso in modo indiretto, l’influenza della colonizzazione greca.

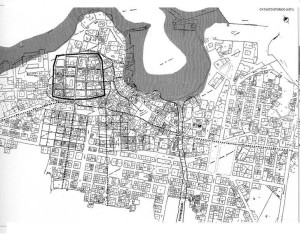

Il sistema dei percorsi in relazione all’ipotesi della formazione pianificata della città di Trani (da G.Strappa, M.Ieva, M. Dimatteo, La città come organismo. Lettura di Trani alle diverse scale, Bari 2003)

Gli insediamenti costieri di approdo sono centri specialistici per il commercio e lo scambio (in questo simili ai nodi di mercato che si formano, spesso, in corrispondenza dei guadi) dai quali si originano sulla costa nuclei urbani in corrispondenza, spesso, con insediamenti di basso promontorio più interni, alla testata di crinali secondari, con i quali viene instaurato lo scambio (non nascerebbe un approdo se non esistesse un’area produttiva da raggiungere).

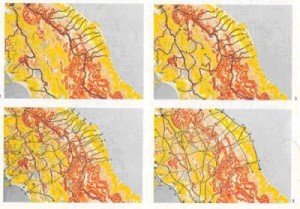

Il sistema dei percorsi e degli insediamenti si forma secondo estesi periodi temporali che corrispondono, schematicamente, ai grandi cicli della storia del territorio:

ciclo d’impianto, databile dal Paleolitico al IV sec. a.C, attraverso il quale si struttura l’intero territorio, da monte verso valle, attraverso percorsi, insediamenti, nuclei protorbani e primi nuclei urbani propriamente detti in corrispondenza dei controcrinali sintetici;

ciclo di consolidamento, databile dall’espansione romana del IV sec. a. C. al declino del IV-V sec. d. C., attraverso il quale si stabilizza la struttura già impiantata, integrata dall’organico strutturarsi dei percorsi di fondovalle e dei relativi nuclei urbani. In realtà processi analoghi e diacronici di grandi strutturazioni dei fondovalle avvengono nei maggiori bacini idrici dell’antichità, come nelle valli del Tigri-Eufrate, del Nilo, del Gange;

ciclo di recupero, individuabile nel periodo medievale tra la fine del IV-V sec. d.C. e la fine del XII sec., durante il quale si perdono le strutture di fondovalle organizzate in periodo romano e si riutilizzano e trasformano le strutture precedenti di promontorio

ciclo di ristrutturazione, corrispondente al periodo dal XIII secolo all’età contemporanea, durante il quale si riorganizzano le strutture di fondovalle parzialmente abbandonate nel ciclo di recupero, con estese opere di bonifiche.

Fasi formative della struttura territoriale dell’Italia centrale (da AA.VV., Cortona, Struttura e territorio, Cortona 1987).

Formazione del sistema delle percorrenze radiali e controradiali in relazione ai fossi della Marranella, di Gottifredi, di Centocelle a Roma sulla base della carta IGM del 1872 ( da G.Strappa, a cura di, Studi sulla periferia est di Roma, Francoangeli, Milano 2012)

4. BIBLIOGRAFIA

Testi di carattere generale:

G.Strappa (a cura di), Studi sulla periferia est di Roma, Francoangeli, Milano 2012

G.Strappa, M.Ieva, M. Dimatteo, La città come organismo. Lettura di Trani alle diverse scale, Adda, Bari 2003

G.Strappa, Unità dell’organismo architettonico, Dedalo, Bari 1995 (on line su questo sito)

F. Farinelli, I segni del mondo, Firenze 1992.

F. Braudel, Civiltà e imperi del Mediterraneo nell’età di Filippo II, Torino 1986

G.Caniggia,G.L.Maffei, Composizione architettonica e tipologia edilizia. 1. Lettura dell’edilizia di base, pp. 203-249, Venezia 1979.

G. Cataldi, Per una scienza del territorio. Studi e note, Firenze, 1977

Come esempi significativi di lettura di organismi urbani particolari si possono utilmente consultare:

G.L.Maffei (a cura di), La casa rurale in Lunigiana, Venezia 1990.

AA.VV., Cortona. Struttura e storia, Cortona 1987

G.Conti, D.Corbara, Per una lettura operante della città. L’esempio di Cesena, Firenze

THE FOUNDATION TOWN OF SABAUDIA: READING AND DESIGN

INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR on URBAN FORM “NEW TOWN: MORPHOGENESIS AND DEVELOPMENT”

Paris, 3-5 July 1998

Gian Luigi Maffei

Giuseppe Strappa

INTRODUCTION

As follows a synthetic reading of the foundation town of Sabaudia and design proposal for the area towards its gateway from the via Appia, to which it is connected. It was put forward by Gian Luigi Maffei, Giuseppe Strappa, Laura Bertolaccini, Tiziana Casatelli, Paola Di Giuliomaria, Amedeo Trombetta, Alessandro Valenti and Marco Valenti and is proposed as a topic for discussion on the design-reading relationship of the modern town. A relationship the speakers maintain wholly identifies it.

The birth of modern architecture in the Roman area continues along the lines of the formative process of types and fabrics, evidently clashing with theories on what is modern in international terms. Due to their unity of conception and speed of construction, towns founded around Rome between 1928 and 1936, especially in the Pontine marshes, clearly express the breaking away of modernity from tradition: Littoria, Sabaudia, Pontinia, Aprilia and Pomezia are modern towns which still respond to those principles of organicity due to a relationship of continuity with their territory, to their hierarchization of streets and to their position and identification of building types. Of these, perhaps Sabaudia is the most significant on account of its innovative character, despite its retention of a traditional town structure.

Sabaudia’s origins are linked to the last phase of an historic cycle that includes the recovery of Roman thoroughfares, the restructuring of the Lepini mountain promontory settlements, originally built for defence purposes, and the formation of rural settlements in the bottom of valleys or plains for productive needs. That is why the foundation of this town must be associated with the conclusion of major anthropization cycles of the territory in the Mediterranean basin, which also led to the reclaiming of the Salonika plain and of the lower Rhone areas, as far as the Algerian Mitidja.

This consideration is of fundamental importance because it enables us to define the nature of the relationship between settlements and their territory symbolically represented through entrances to towns.

TERRITORIAL ORGANISM

The first territorial anthropization plan cycle that generated the settlement of Sabaudia took place due to the immigration of Italic nomads in waves from northern regions around the first millenium B.C. The structure of routes took place according to a “territorial type”, which is quite constant in central Italy: from paths along the Appeninic main ridge towards (often orthogonal) secondary ridges coastwards. Subsequently, paths parallel to the orographic main ridge formed along hill slopes, giving rise formerly to higher and then to lower promontory settlements, until the valley bottom was colonized.

This territorial appropriation process can clearly be read in the Lepine mountain ridge according to a layout which, from north to south, initially led to the formation of Neolithic settlements and, afterwards, to the structuring of the Latin-Volscian territory with the construction of the fortified towns of Artena, Segni, Cori, Norba Sezze and Priverno; the latter was built along the junction of Italic colonization and the boundary of the Lepine ridge.

The subsequent piedmontese trade route was followed by the Roman colonization of the valley bottom with the foundation of a stable civil organisation and an organic territorial form based on roads (chiefly the Appia axis) parallel to the Appenine ridge, where coastal and productive centres were linked by a structured thoroughfare system. After the decline of the late Ancient World and the Medieval revival of settlements built at an altitude (phase to which the current organisation of Lepine settlements corresponds), the drainage and restructuring of the Pontine marshes (the period from the late 19th Century to the present date) corresponds to the last territorial anthropization process cycle.

Despite the fact that it was entirely planned in 1933, and therefore is a “critical” product as opposed to the “spontaneous” foundation of other, previous territorial settlements, Sabaudia thus continues along the lines of transformative processes with its territory:

– spatial continuity due to the grid of roads and territorial junctions hierarchized from the bottom of the piedmontese valley and from the Appia, and structured by means of the so called “miliare”modular system.

– historic continuity as the last phase of a territorial anthropization process which proceeds from the mountains towards the valley, according to cycles and phases typical of every Latian territorial settlement process.

– typological.process continuity in that the form of the town “pertains” to its historic phase, which is that of progressive reutilization of the arable areas of plains and valley bottoms in order to recover and reuse areas civilized in ancient times which then declined during the latter part of the era, parallely, as previously mentioned, to other similar areas in the Mediterranean basin

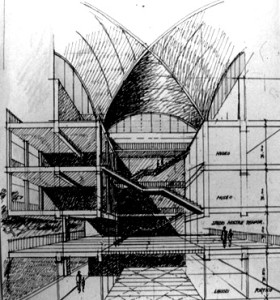

URBAN ORGANISM

Sabaudia’s urban organism, as in the case of other reclaimed rural centres, is the result of territorial routes. A rural settlement that sprawled into its arable land, Sabaudia is a farming village highly hierarchized by its singular (orographically discontinued) position and by its road network (linked to the coastal network) conferring upon it its role as a territorial node: “It is not a town”, wrote Piccinato, “but a farming village indissolubly connected to its territory and arable land”.

This structure is polarized, in its centre, by (special) outbuildings forming the begining and end of its streets and, on its outskirts, by special “antipolar” constructions grouped together according to typological affinities. A choice opposed to the monofunctional areas philosophy of Modern Movement ideology.

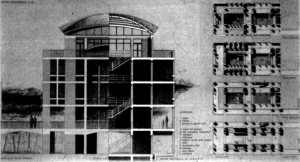

Polar buildings (see figure 1) are concentrated in the area surrounding the town square (town hall, post office, theatre-cinema formerly Fascist headquarters, trade unions, formerly Ex-servicemen’s Association, etc.).

The building formerly used as a bus station was scheduled to polarize the road link to Terracina. Special antipolar buildings (former hospital and maternity and children’s hospital in the north eastern corner, farm estate and foresters’ centre to the south east, Piave barracks and dockyards to the south east etc.) are mainly distributed in the outskirts of the original town and, as Sabaudia expanded, they gradually assumed a new polar role, as in the traditional town.

In the hierachization of poles, a key role is played by its town square and orthogonal street network, linking the thoroughfares of corso Principe di Piemonte, corso V. Emanuele III and corso V. Emanuele II, centralizing axes. The latter is fundamental as a continuation of one of the coastward routes departing from Appia. It is polarized, at the other end, by its entrance to Toigo square and is completed by parallel pedestrian footpaths, which become porticoes after Oberdan square.

Among secondary polarities, that of Oberdan square acquires special value in that it terminates viale Regina Elena, whose importance lies in the fact that the main road between Sabaudia and Terracina leads into it.

AGGREGATIVE ORGANISM

The architects behind Sabaudia did not draw up a simple town plan but entirely planned the town as a fabric of buildings lining streets; they only conceived the shapes of buildings according to the lay-out of streets and avenues. The sprawling of buildings from the centre towards the countryside expressed the lack of a net boundary with the countryside at the back, to which the town is linked by the road network of the reclaimed Pontine marshes.

The building of multifamily dwelling houses in the foundation town (which directly concerns our design) is usually distributed in threes and triply or dually structured, almost always with two or three dwellings per stairwell. his plan is retained in the new constructions along corso Vittorio Emanuele II:

BUILDING ORGANISM

Mention has been made often of the fact that Sabaudia’s architecture leads back to the very heart of modernity. However, unlike many towns built at the time, the old part of Sabaudia is discreet, understated and hidden under numerous layers of modernity. What stands out in the interpretative originality of the new part of Sabaudia is the organic nexus between building and fabric and between building distribution and streets. In this, the types used are un update of traditional forms: the town hall, in which the row structure with hierarchized rooms is organised by corridors leading into the courtyard polarized by the stairs, or the religious complex in Regina Margherita square, where the church’s nodal room is the continuation of a town axis reaching the altar from the main entrance, and the nunnery is organised, as in convent plans, along a path starting from the presbyterium.

Furthermore, the nature of building elements and structures in Sabaudia is a modern derivation of the Roman plastic-wall cultural area. The majority of buildings are obtained from the composition of walls which can be interpreted as load-bearing and closing at the same time. This peculiarity is more noticeable (solider and more organic) when constructions are really built in supporting masonry whereas, when they are built with reinforced concrete frames, it is harder to interpret the nature of buildings from the partial exposure of the reinforced concrete framework, regardless of whether or not they are in brick, conferring upon centres a degree of seriality (see, for instance, pilotis-porticoes).

Special buildings came into being together with their fabric and their distribution relates organically to the town’s structure: not by chance the fabric design and building plan in Sabaudia arose contemporaneously, conceived to update the town’s heritage.

THE DESIGN: CONTINUING SABAUDIA

The design of the piazza Toigo, Plozner park, piazza Oberdan areas is based on some fundamentals that conditioned its conception and guided its development:

1. The spatial continuity between territorial scale, the town scale, its urban fabric and its buildings;

2. Its historic continuity in the formation of its anthropized space between the major territorial structuring cycles (in the various phases into which it can be broken up: structuring, consolidation, recovery and restructuring) linking natural resources to the ways in which mankind lives space.

3. Building continuity in the relationships that connect building process products, from elements to structures, systems and building and civic centres.

4. Continuity in the readability of the built environment (and therefore also in language, the intentional product of the building production critical stage) which does not mean imitation and assonance with pre-existing ones, but consists of the visible result of a continuation and transformation process affecting all built environment characteristics (inner distribution and streets, static building structure of constructions and nature of structures used in the cultural area).

The concise reading that follows, together with its subsequent conclusions re-recorded in the design, is ordered according to the continuous formative process steps that produced the anthropization of the Pontine territory, the formation of Sabaudia and the hierarchization of civic areas and the construction of buildings.

Despite considering Sabaudia as an aware, “artificial” product of a highly critical stage of architecture such as the passage to mature modernity, we therefore wished to acknowledge the town’s formation as the product of “long periods of time” structuring its pertinent territory in stages.

These choices are expressed in the following design indications.

Building is structured by streets and nodes (meaning by “node”, on all scales, the intersection of what is continuous or discontinuity of what is continuous).

STRUCTURE OF STREETS

The building and architectural centres designed arise from the streets, as in the traditional town (we have attempted to show that Sabaudia is modern and not modern at the same time).

These streets are hierarchized according to two complementary roles, which are both closely connected to the existing town:

1 – Porticoed routes (centralizing axes) forming the main structure of streets in the new design; they continue along existing streets or as generating axes in the new design. These routes form an integral part of building organism:

– routes adjacent to the axis of corso Vittorio Emanuele II; this street joins up and continues the alignment and structural pitch of porticoed building constructed immediately after the Second World War. Existing porticoes are to be repaved to blend them in with the new designs according to a geometric scheme highlighting the continuity of the structural pitch between what existed previously and new action.

– routes facing Oberdan square; this routes forms the margin of the square and orients temporary residences.

2 – Routes off the ground follow the development of porticoed streets on the ground and establish relationships between the specialized rooms of new buildings that serve to compensate and are similar or complementary to ground floors (like mezzanine floors in traditional building). On account of thier function, these streets also form an integral part of building centres.

3 – Dividing routes are dividing lines between building and public civic areas; these routes cropped up spontaneously in the original town, even though they were often discontinuous and haphazard when basic building did not have pertinent areas, forming the necessary complement in the centralizing – dividing axis dyad. These routes help to indicate the nodal points of special buildings.

– route adjacent to the Plozner park, joined to the porticoed route surrounding the archive museum building; together with the parallel main route, it forms a series of modular parterres which can be potentially used as spaces for rest facilties;

– route adjacent to Plozner park behind dwellings on Oberdan square;

– restructuring route of areas behind buildings in existing lines on corso Vittorio Emanuele;

4 – secondary centralizing routes to the sequence of Oberdan garden park-square civic areas; they are routes that organise open areas, cross the former bus depot and can continue, as pedestrian footpaths, along the alley (whose continuity has to be restored by eliminating current barriers) parallel to viale Principe Biancamano. These routes are polarized:

– by the new hawkers’ market square at the end of via Amedeo II;

– by the former bus station building;

– by parking facilities at the edge of Plozner park on via Principe Amedeo;

– by the new viewpoint overlooking the National Circeo Park to be built at the end of the street parallel to via Biancamano in a raised area enabling Sabaudia’s orography to be perceived. this routed could flank the hill reaching Braccio dell’Annunziata on Sabaudia Lake and continue in the direction of the chapel of S. Maria della Soresca, forming a pedestrian circuit.

ROUTE NODES AS NODAL POINTS FOR BUILDINGS

The intersection of routes generates, as in the foundation town of Sabaudia (and in the traditional town), nodal points that are hierarchized according to the type of route and centrality of its topological position.

These nodal points are not only hierarchized civic areas but also represent elements forming buildings themselves, confirming the indissoluble continuity between the formative process of civic areas and spaces inside special buildings. In other words, the area is “knotted” inside the building according to laws dictated by the civic centre, generating nodes which at various degrees are contemporaneously distributive and building, readable by means of the architecture of buildings.

These nodes are:

– new special building nodes destined for the Pontine Marshes and Reclaiming Museum and Historic Archive. They are formed by the intersection of pedestrian footpaths along the axis of corso Vittorio Emanuele (portico adjacent to the street that can be passed by vehicles and the applicable route adjacent to Plozner Park) and orthogonal pedestrian footpaths on the Oberdan square side (portico of special residences and applicable path adjacent to Plozner park). These footpaths are doubled off the ground by the overhead passageway linking constructions on the sides overlooking major civic areas (squares and streets) forming an integral part of the building. These nodes are based on the assumption that special building is traditionally connected to streets; their junctions trigger off the nodal points of buildings. Even though the museum-archive row building is linked to the repetition of openings along corso Vittorio Emanuele, these intersections hierachize the inner space generating continual spaces on various floors of the museum and entrance hall.

The cross vaulted roof (intersection and major structural node) indicates the existence of a

specialized area (intersection and major distributive node).

– node of the new hotel facilities building intended not only as reception facilities of the hotel structure but also as a conference hall and outdoor areas for seminars. They are formed by nodal points generated by the shifting of the two overlapping routes along corso Vittorio Emanuele. This node, which is hierachically speaking subordinate to the nodes of the museum-archive building, terminates the major footpaths of the new design and understatedly indicates to visitors, entering Sabaudia from the Appia, the organic structure of relationships between routes and buildings.